- Upstream Ag Insights

- Posts

- Mindware: 33 Mental Models for The Modern Agribusiness Leader

Mindware: 33 Mental Models for The Modern Agribusiness Leader

Essential frameworks for agribusiness leaders working in crop inputs, ag retail and precision agriculture.

Introduction

Agribusiness professionals operate in a world full of volatility, complexity, and constant change.

Commodity price swings, regulatory shifts, changing customer demands, and technological evolution create a landscape where uncertainty is the norm, not the exception.

Since joining the industry, one thing has become clear to me: whether I have interacted with a senior executives, a marketing manager, or an elite agronomist, what separates the best from the rest in navigating these challenges is how they think.

Just like a carpenter has a tool belt with a hammer and drill, or a golfer has fourteen clubs to use depending on shot demands; high-performing agribusiness professionals need a collection of mental tools ready to be deployed for any situation they encounter.

I think of that toolset as Mindware.

Note: The full contents of this article are being published as a digital guidebook and will be available in July 2025.

Mindware

The term Mindware was popularized by psychologist Richard Nisbett to describe a combination of mental models, reasoning strategies, and frameworks that help people think clearly and make better decisions.

It's effectively cognitive software— the internal code we run to solve problems, analyze trade-offs, and interpret the world.

Mental models are at the heart of mindware. They are simplified representations of how the world works— patterns, principles, and frameworks that help you see clearly in complex environments. They’re the shortcuts to insight and the differentiator in demanding situations and important decisions.

As Charlie Munger, the godfather of mental models, put it:

“Developing the habit of mastering the multiple models which underlie reality is the best thing you can do.”

The more useful models and frameworks you hold, the better your judgment.

Mental models come in many forms, but for me they broadly fall into three core categories.

Each plays a different role in improving how we think, reason, and act:

1. Descriptive Models

These models help us understand systems, processes, and relationships in the world. They’re rooted in disciplines like physics, biology, economics, and systems thinking. In agribusiness, these are especially useful for simulating dynamics, forecasting outcomes, and understanding interdependencies. Examples include the law of diminishing returns, entropy, creative destruction, inertia and many more.

2. Cognitive Models

These come from psychology and behavioral economics. They explain how our brains shortcut decisions, fall into traps, or misjudge information. As agribusiness becomes more data-rich and decision-heavy, avoiding cognitive bias becomes a major differentiator. Some of these are covered in 25 Concepts for Improved Career Outcomes in Agribusiness. Examples include things like inversion, incentives, Occams Razor, Loss Aversion, and many more.

3. Strategic Models

Arguably, these models could fall into #1. They help guide strategic decision-making, resource allocation, and competitive positioning. They’re used in business, and often come from game theory, or military strategy. But they are crucial for thinking strategically about business, products or careers.

When our mental models and frameworks align with reality, they help us make better decisions. But when they’re misaligned — when we operate based on faulty assumptions or cognitive bias — they cause problems of their own.

For agribusiness professionals, whether in crop inputs, equipment, ag retail, or startups, having strong mindware is a force multiplier. It enables faster learning, sharper thinking, and more confident action — even when conditions are challenging.

This guide curates a set of mental models and frameworks that I’ve found particularly useful from all three categories above, with a heavy emphasis on strategic models.

Some are borrowed from strategy leaders, some from biology and some I created when applying concepts from the industry.

These models are adapted to the unique dynamics of agriculture and aren’t abstract strategy concepts.

They’re practical lenses designed to help you lead, decide, and operate more effectively in one of the most complex industries in the world.

Each of the 33 frameworks includes:

A Corresponding Illustration (where applicable)

Overview of the Framework

Application to Agribusiness

Key Takeaway for Agribusiness Professionals

Index

The Red Queen Effect

Overview

The Red Queen Effect is a concept from evolutionary biology that explains how species must constantly adapt and evolve— not just for progress, but to simply maintain their current position in a changing environment.

The term comes from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, where the Red Queen tells Alice, “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.” In nature, this means organisms must continually evolve to survive against ever-evolving competitors, predators, and parasites.

The Red Queen Effect is often used to describe competitive dynamics— especially in fast-moving industries. Companies must continually innovate just to retain their market position because competitors, technology, and customer expectations are always advancing.

Applied to Agriculture

Example: An ag retail company introduces a premium crop scouting service that uses drones, imagery, and digital reporting tools to deliver faster, more accurate insights to farmers. It quickly becomes a differentiator— farmers see value, yields improve, and the retailer gains market share and manages margin erosion.

But within two seasons, competitors begin offering similar services. And some take it a step further and partner with companies like Solinftec and bundle scouting, product and the application service to deliver an entirely new experience to the farmer.

Suddenly, what was once a competitive edge is now expected, and in some cases, has been surpassed.

To maintain relevance, the original retailer must continue evolving— integrating new tools and system, layering in See & Spray prescriptions, and hiring entirely new teams to compete and differentiate.

Takeaway

Ongoing innovation isn’t about getting ahead one time— it’s about having the mindset, or the company culture, to continually find ways to do so.

Roger Martin’s Playing to Win Framework

Overview

Roger Martin’s Playing to Win framework defines strategy as a set of integrated choices that position a business to win. It revolves around five core questions:

1. What is our winning aspiration? Defines the end goal— what success looks like.

2. Where will we play? Identifies the specific markets, customers, and segments to focus on.

3. How will we win? Articulates the unique value proposition and competitive advantage.

4. What capabilities must be in place? Specifies the activities, competencies, and assets required to execute.

5. What management systems are required? Ensures alignment of processes, incentives, KPIs, and organizational structures.

The strength of the framework is in forcing clarity and alignment between ambition, focus, differentiation, execution, and measurement.

Application to Agriculture

Agribusinesses often drift into reactive mode— serving everyone with everything. The Playing to Win framework challenges this by demanding focused choices:

An independent retailer might define its aspiration as becoming the most trusted advisor to progressive row crop farmers in the Midwest.

- Its “where to play” choice could focus on 1,000–5,000 acre farms in a five-county region growing corn and soybeans.

- Its “how to win” could be through proprietary agronomic programs and integrated service offerings— not price or scale.

- The capabilities might include top-tier agronomists, a detailed training approach for their team, a new approach to service, and a uniquely thought out supply chain.

- Management systems would align incentive structures, data tracking, and service models to reinforce the strategy.

This clarity helps avoid generic strategies like "grow market share" or "become more innovative" without knowing who you're serving, how you're different, and what you need to be excellent at.

Takeaway

Strategy is not a vision or a plan— it's about making hard, integrated choices that define where to focus and how to win.

In agriculture, with rising complexity and margin pressure, companies that clearly articulate their strategic choices and align their teams and systems around them, will be far more likely to create loyal customers and enduring value.

Hierarchy of Agronomic Needs

Overview

Adapted from Maslow’s hierarchy, this framework structures what a grower needs to succeed based on foundational needs up to more “elevated” outcomes.

The Hierarchy of Agronomic Needs is a framework that helps illustrate how farmers prioritize different crop inputs based on necessity, particularly through avrying economic conditions.

Applied to Agriculture

At the base of the pyramid are Foundational and Functional products— things like land, seed, fertilizer, and basic crop protection. These are used every year regardless of price or weather outlook. These are essential.

Then we move to Functional Needs— herbicides, insecticides and macronutrients like N and P. These are not required to grow a crop, but the average farmer wants access to these tools and products every year.

Moving up the pyramid, we reach Optimization Options (like micronutrients or variable-rate tools), products that a farmer can go without, but are beneficial.

Finally we get to Elevated Outcomes— products like biostimulants, which tend to be used only when prices are strong, yield potential is high and farm income has been positive.

Farmers are more likely to cut back on products higher in the pyramid during tough years.

But with strong positioning, education, and integration into essential use cases, companies can move products down the pyramid— making them feel more like “must-haves” instead of “nice-to-haves.”

Takeaway

Input manufacturers, agtech companies and ag retailers should focus on actions that move their products down the pyramid— closer to default use and foundational or functional. That means deeply understanding where and why they work, tightly positioning inputs to specific agronomic problems, clearly communicating economic return, and tying usage to familiar systems or foundational practices. The closer a product gets to being seen as essential, the more resilient its demand becomes regardless of the weather, prices or overall commodity cycle.

Innovation Adoption Framework

Overview

Innovation adoption in agriculture is best understood through six interconnected concepts that shape whether a new product or practice gains traction:

1. relative advantage

2. compatibility

3. complexity

4. trialability

5. observability

6. adoption chain risk.

These factors don’t just influence farmer decisions— they define the environment in which agribusiness success or failure unfolds.

For agribusiness professionals, recognizing and responding to these six dimensions is important. Product development, go-to-market planning, channel partnerships, support structure and marketing must all be shaped with these principles in mind. Companies that do so will increase their odds of achieving meaningful, scalable adoption.

Applied to Agribusiness

Relative Advantage This refers to how much better the new technology is compared to existing options— whether in absolute yield, cost, labor efficiency, or risk reduction. For example, auto steer was widely and rapidly adopted because it improved efficiency and costs (less overlap) and decreased mental strain compared to human control.

Compatibility This assesses how well the innovation fits into the farmer’s current system, values, and beliefs. A precision ag tool might be highly effective but will fail if it doesn’t align with the operator’s skills, risk tolerance, or farm assets.

Complexity The more difficult a technology is to understand and integrate, the slower it is adopted. Farm management software was not adopted as readily as anticipated because it was tedious and complex to use and derive value from.

Trialability Farmers value low-risk experimentation. Products that can be “eased into”with low-barrier ways to test new offerings and build confidence are key before getting a farmer to commit.

Observability If the results of using a product are visible and measurable (eg: fewer weeds, lower harvest loss, or more uniform emergence), adoption increases. Inputs like biostimulants or software tools often suffer from lower observability, requiring creative strategies (eg: tissue testing) to demonstrate value.

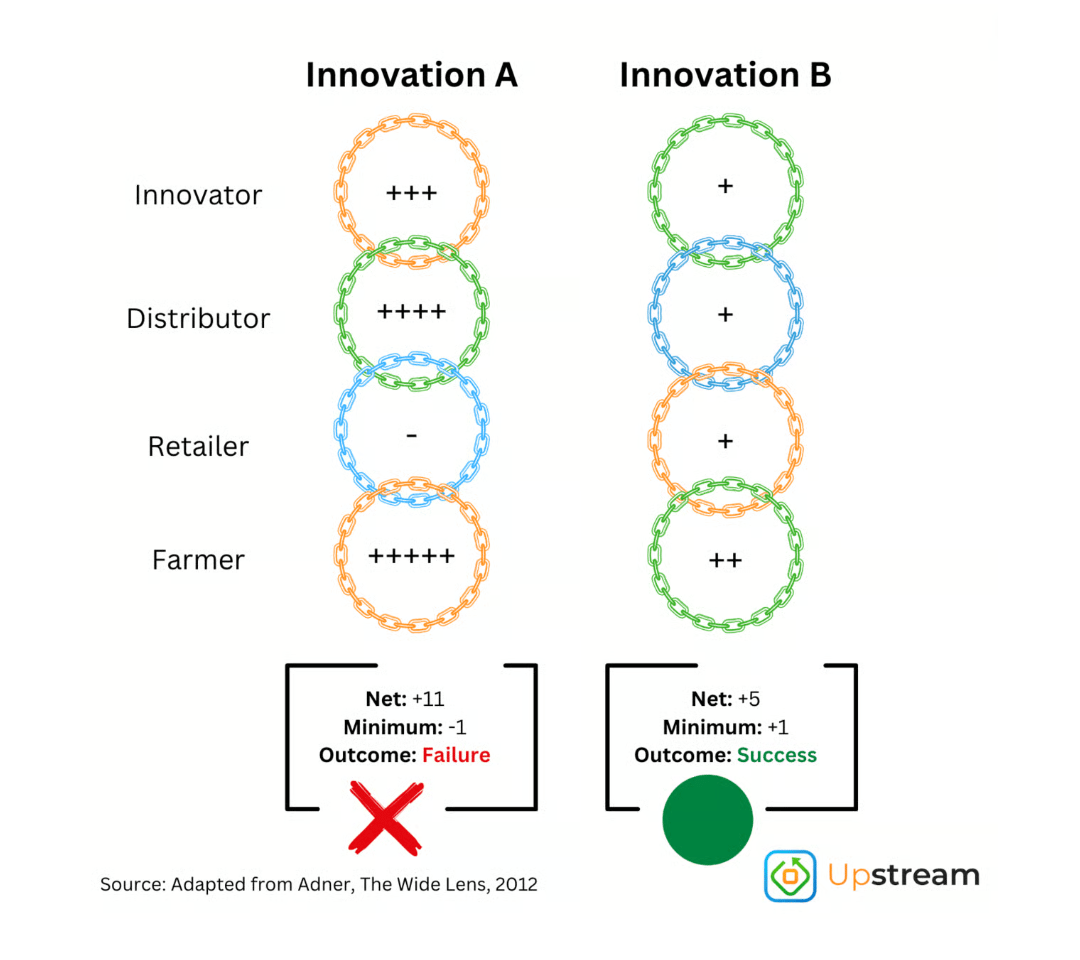

Adoption Chain Risk (from Ron Adner’s The Wide Lens) Many agricultural technologies depend on multiple players to reach the farm: input manufacturers, retailers, agronomists, and channel partners. If any link in this adoption chain isn’t aligned— due to incentives, education gaps, or workload aspects— the innovation stalls, regardless of how beneficial it is for the farmer. See image below.

Takeaway

Innovation adoption in agriculture is not just about delivering a better product— it's about removing friction across the entire system. Agribusiness professionals must think beyond farmer economics and embrace a systems approach:

- Design for simplicity and support.

- Enable trials and showcase results visibly.

- Build channel incentives and reduce perceived risk.

- Align product positioning with the operational context and behavioral tendencies of the farmer.

Adoption isn't won in the field alone— it's orchestrated early and across the entire value chain.

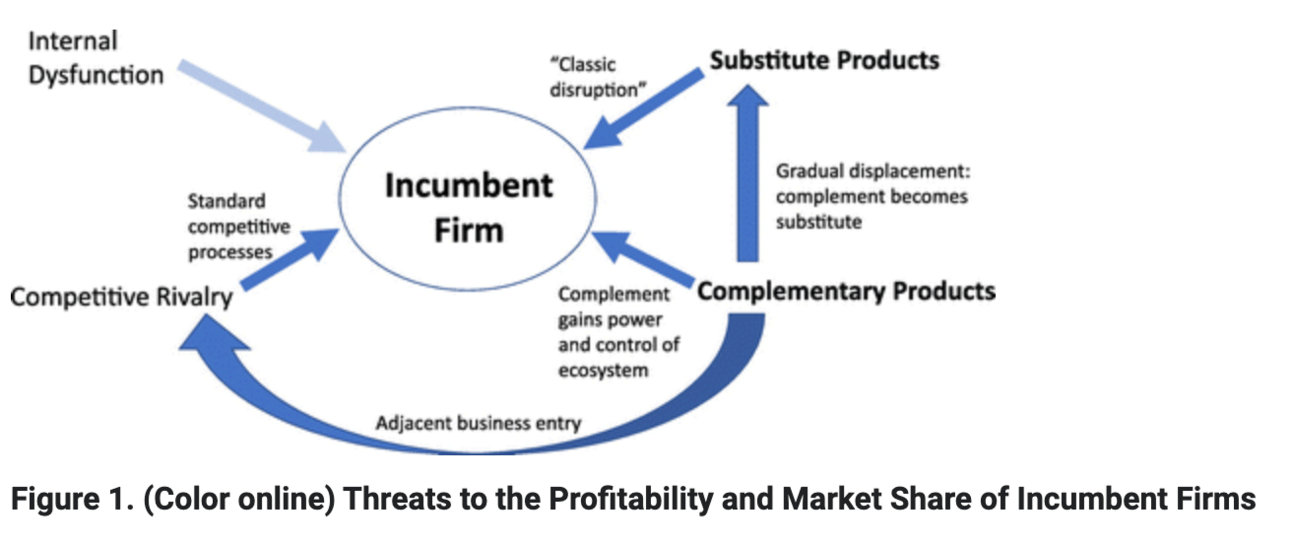

Ecosystem Disruption and Disruption Through Complements

Source: Adner, Lieberman: https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/10.1287/stsc.2021.0125

Overview

Disruption through complements occurs when the value of a core product is undermined not by a direct competitor, but by improvements in complementary innovations— products or services that must work together with the core product to create value.

In Ron Adner’s framework, disruption doesn’t always happen head-on. Sometimes, the competitive threat arises indirectly, when another firm improves a complement in a way that:

- Reduces the need for the original product

- Changes the adoption dynamic of the ecosystem

- Shifts customer value away from the incumbent

Applied to Agribusiness

Disruption through complements happens when innovations in complementary products — not the core product itself — undermine the value or relevance of that core product. In agriculture, this means that a product can lose its competitive position not because it got worse, but because the tools or technologies that work alongside it improved in ways that reduce the need for it.

A notable example is the relationship between herbicides and sprayers.

Traditionally, the use of broad-spectrum herbicides, broadly applied was essential for managing weed pressure.

But with the rise of precision sprayers (eg: See & Spray from John Deere or Greeneye Technology), the sprayer becomes the innovation that shifts the value equation.

Now, the ability to selectively target weeds using cameras and AI reduces the volume of herbicide needed or commoditizes the differentiation of the herbicide itself, which is traditionally herbicide features like tank mixability, soil residual, and crop safety for example. Precision application shifts this.

In this case, the sprayer is the complement that disrupts the herbicide market. The herbicide itself may still be effective, but the improvement in the complement (the sprayer) changes the economics, value pool, and product requirements, undermining the traditional value proposition of the herbicide.

Complement disruption can be further reinforced by equipment companies by adding weed mangement tools to combines (eg: Harrington Seed Destructor) or when the information about the field, such as where the weeds are, the density and size, is all captured by the camera augmented machines.

The Takeaway

As complements evolve, they can redefine what is necessary, valuable, or economically viable, shifting the locus of influence and changing the value pools, economics and ultimately, power positions within the world of crop protection, reshaping what entities can gain revenue from the farmer.

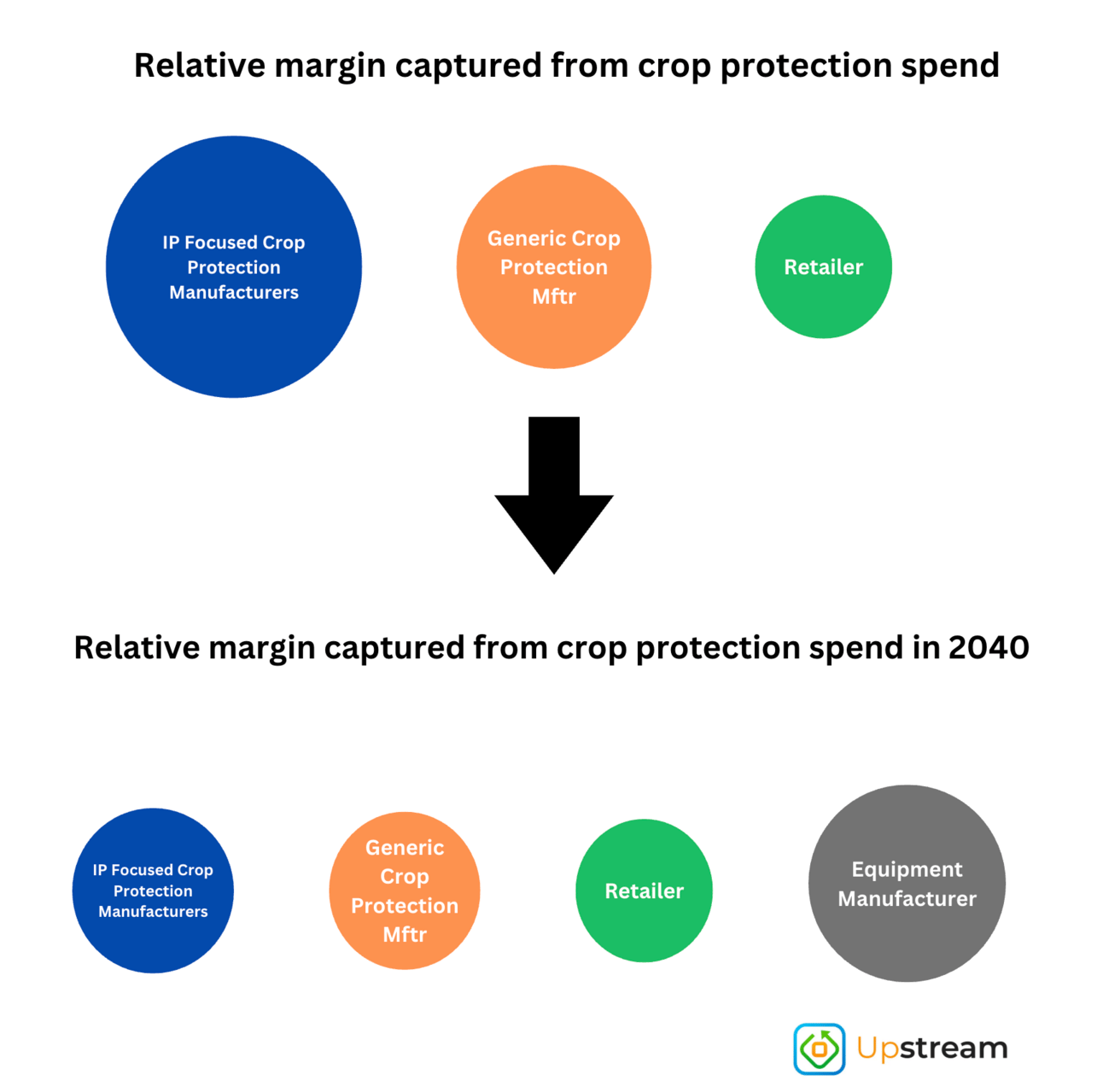

Commoditize Your Complement

Overview

Coined by Joel Spolsky, the idea is simple:

To maximize your own value, you want the products or services that complement yours to be cheap, accessible, and standardized.

A complement is anything that increases the demand for your core product. For instance:

- Printers and ink are complements. If printers are cheap, people buy more ink.

- For Microsoft Windows, hardware (Intel chips) is a complement. Cheaper chips meant more PCs, which meant more Windows licenses.

By commoditizing the complement (making it less differentiated or more widely available), a company can increase the demand for their own differentiated offering — and maintain pricing power over it.

Application to Agriculture

In agriculture, complements are everywhere: agronomy services for inputs, data to support input usage, equipment to complement crop protection products, credit to drive crop protection product demand, and more. Strategic use of this principle shapes industry dynamics.

Let’s apply it specifically to herbicides and sprayers.

Currently, sprayers are complements to herbicides, with value primarily derived from the herbicide’s differentiated characteristics (efficacy, crop safety, residual, etc.). However, as precision spraying technologies advance, with the ability to detect and target weeds in real time, the sprayer becomes the primary control point. This shift commoditizes the herbicide, reducing the relevance of its individual differentiators and eroding the margin potential for crop input companies, shifting dollars to the equipment company (theoretically). Over time, this dynamic may extend to other input categories as hardware capabilities increasingly dictate performance.

Another application is to gene editing technology and genetics for seed companies.

Takeaway

If you want to increase demand and pricing power for your core product, identify its key complements — then make those complements cheaper, simpler, or more accessible if you can. In doing so, you shift value toward your core offering. In ag, this might mean commoditizing gene editing technology if you own genetics and market access (like Corteva).

Control Points in Software

Overview

In software, a Control Point, as coined by Tidemark Capital, is the system around which all other workflows revolve. It’s the platform users depend on to run their core operations— the first tool opened in the morning and the last one closed at night. In business software, control points usually fall into two camps:

Front office: Where revenue is generated and customer interaction occurs (CRM, e-commerce, contracting)

Back office: Where operations, finance, and compliance are managed (ERP, accounting, inventory)

The control point forms due to many reinforcing aspects:

- Data gravity (the more data that lives in a system, the harder it is to leave)

- Workflow entrenchment (critical daily tasks are run through the system)

- Ecosystem centrality (the product becomes the hub for other tools)

- APIs and integrations that make the software the connective tissue for operations

- Unique insights or analytics derived from proprietary data models

Owning a control point gives a software company significant power: it drives adoption, enables upselling of adjacent features, vertical expansion and is extremely difficult to displace. If a software provider does not own the control point, they’re at the mercy of the one that does. Their product becomes a feature, not the foundation.

Application to Agriculture

In row crop agriculture, the true control points are not agronomic software platforms or farm management tools. They are transactional and financial systems— the ERPs used by ag retailers, and the merchandising software used by grain originators.

These systems sit at the center of daily commerce: input ordering, invoicing, credit, product delivery, grain contracts, and payments.

AgVend, for example, is not trying to be another agronomy tool. It’s targeting the front-office control point by digitizing and simplifying how ag retailers manage customers, order, forecast, pay communicate and more. By embedding into these workflows and becoming a platform retailers rely on to drive revenue, it positions itself as the interface for action. That’s a control point.

Those who own this layer of infrastructure are best positioned to layer on new features, unlock data-driven services, and generate long-term enterprise value.

Takeaway

The software battle in ag is for control points. If your software doesn’t sit at the center of daily transactions or operations, you're building a feature, not an operating system. The companies that win will be the ones who become foundational to how ag retailers, grain originators, equipment dealers and farmers work. Own the control point— and you own the ecosystem.

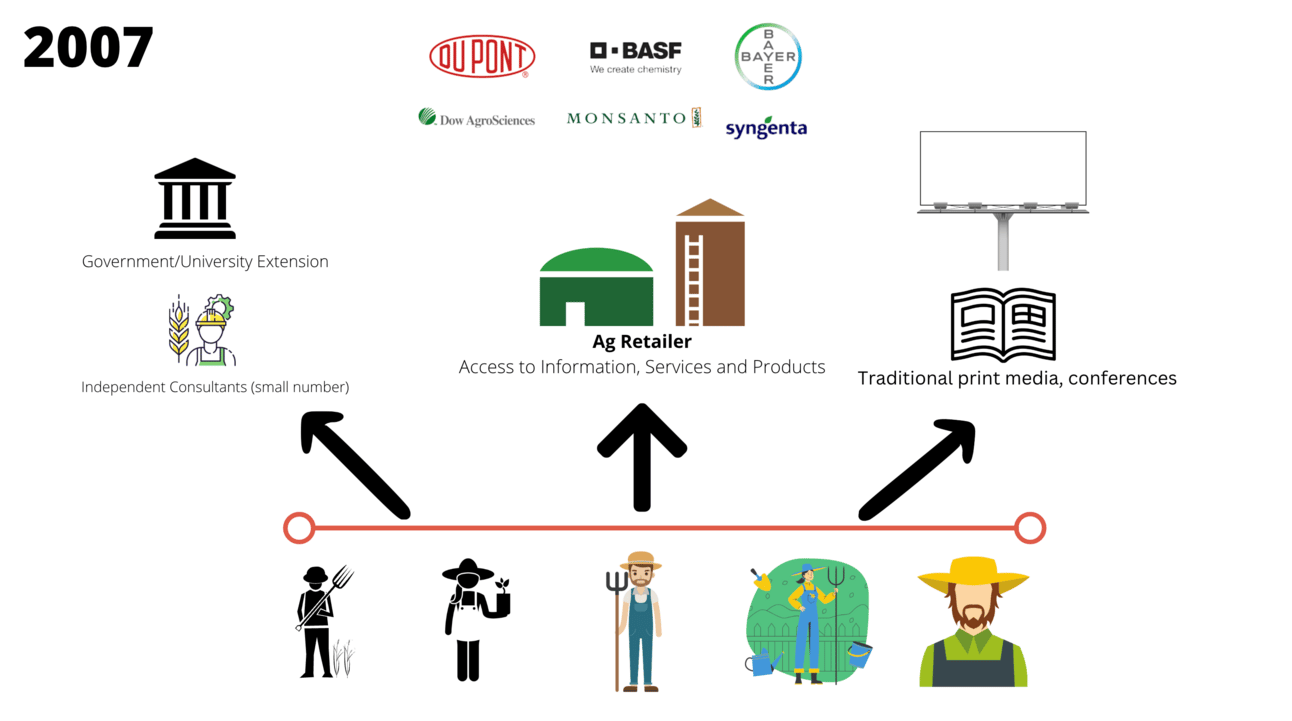

Influence Erosion

Overview

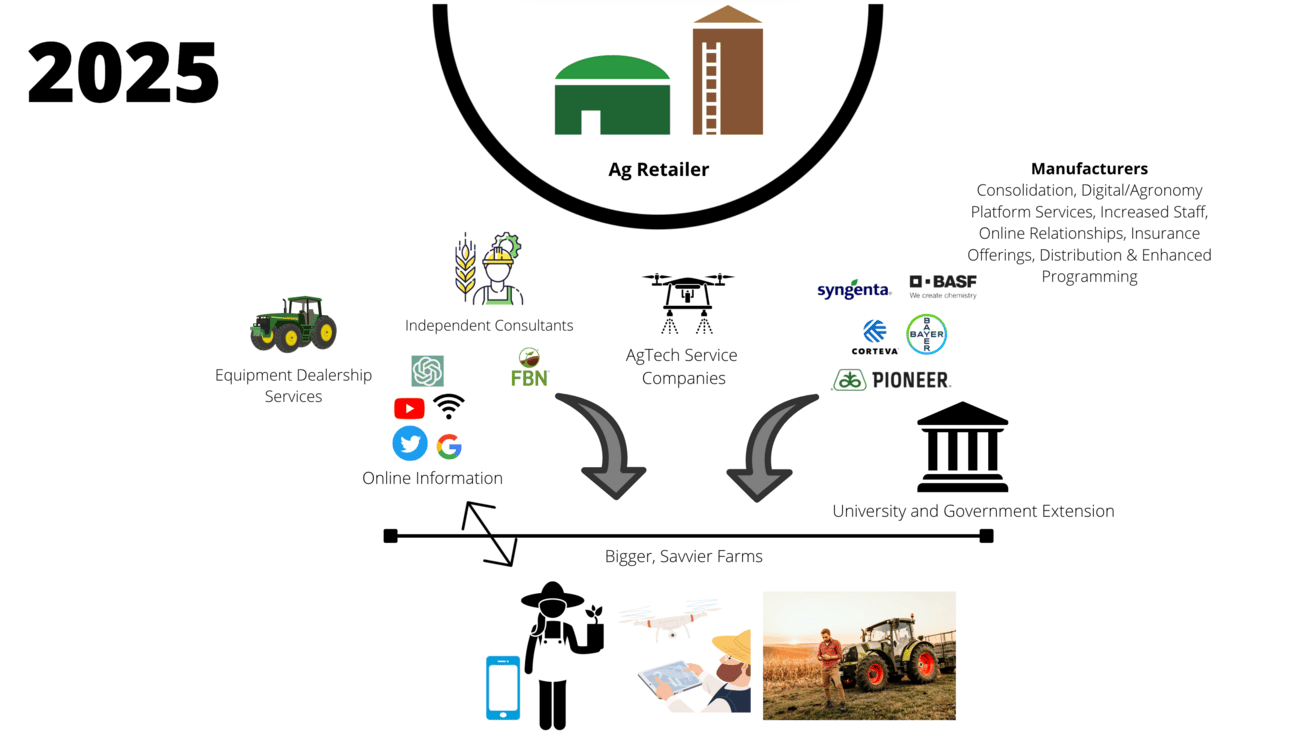

Influence erosion refers to the gradual loss of an ag retailer’s ability to shape and guide farmer decisions—particularly around product choice, services, and loyalty—due to a shift in where farmers get trusted information, support, and value.

Historically, ag retailers held a dominant position through bundled services, product access, credit, agronomic advice, and geographic proximity. But today, that influence is being eroded by:

- Direct-to-grower relationships from manufacturers

- Proliferation of agtech firms, independent consultants, and data platforms

- Digital marketing and analytics enabling tailored, scalable outreach from suppliers

- A collapse of information asymmetry due to social media, search, AI, and price transparency platforms

Influence is no longer guaranteed by geography or product access. It must be earned and re-earned across a growing number of touchpoints, in a market where the farmer has far more optionality than ever before.

Moving from this:

To this:

Implications for Agribusiness

For ag retailers, influence is the factor that connects products and relationships to profitability. Without influence:

- Margins shrink due to commoditization

- Product differentiation erodes

- Share of wallet declines

- Long-term loyalty weakens

All of this starts to crack the relationships with suppliers and their emphasis on the channel.

Entities that own the relationship, data and farmer trust will increasingly shape the market. If a retailer is no longer the farmer’s first call, they default to an order taker, not a decision influencer.

Understanding how influence erodes is central to maintaining relevance and capturing margin in a changing agricultural ecosystem.

Takeaway

Ag retailers are at risk of losing influence. As manufacturers, agtech firms, and information platforms build tighter grower relationships, and farmers grow in size retailers must evolve: invest in new tools, vertically integrate, offer differentiated services, and rethink how value is delivered and communicated. Influence is no longer guaranteed— it must be consistently earned.

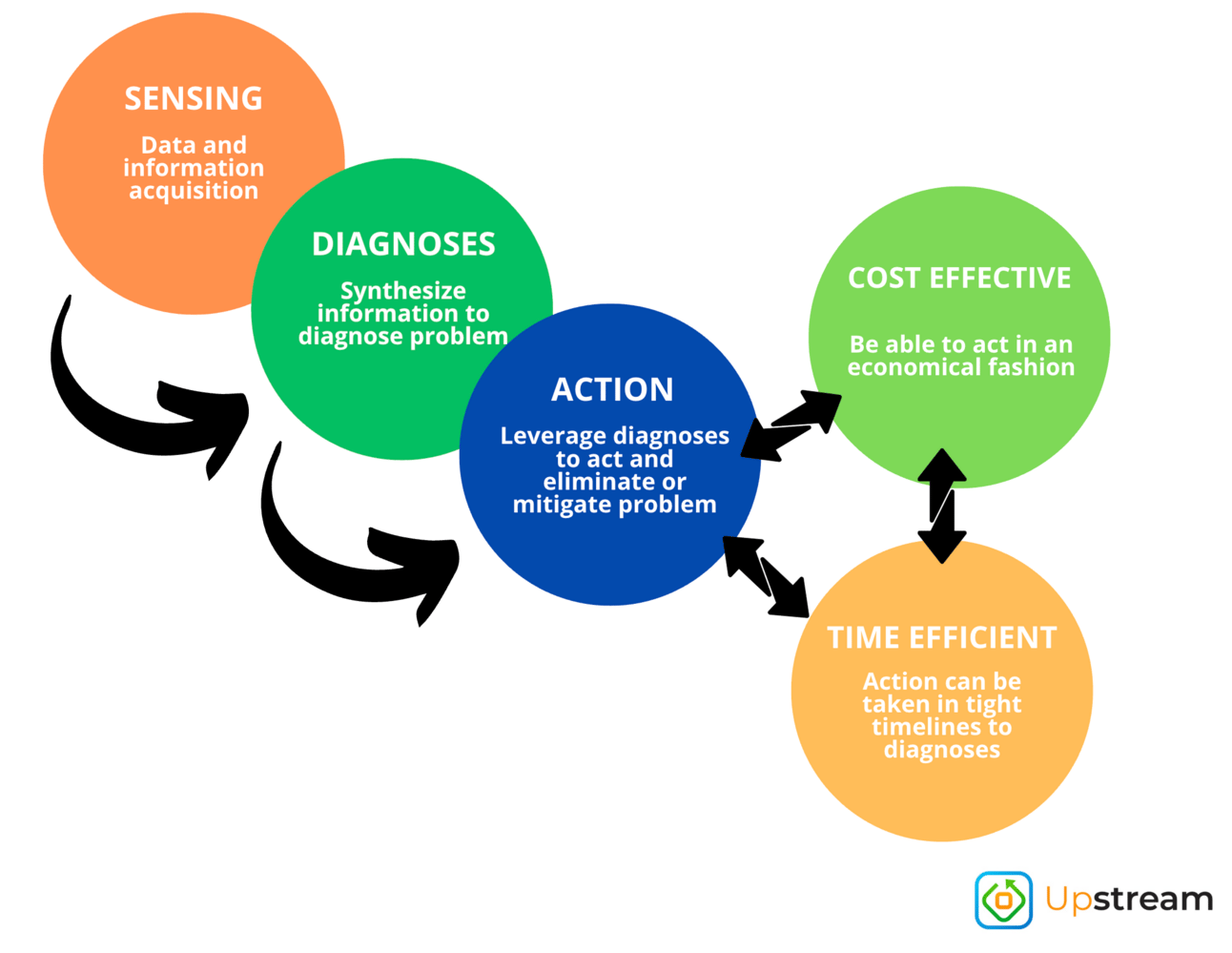

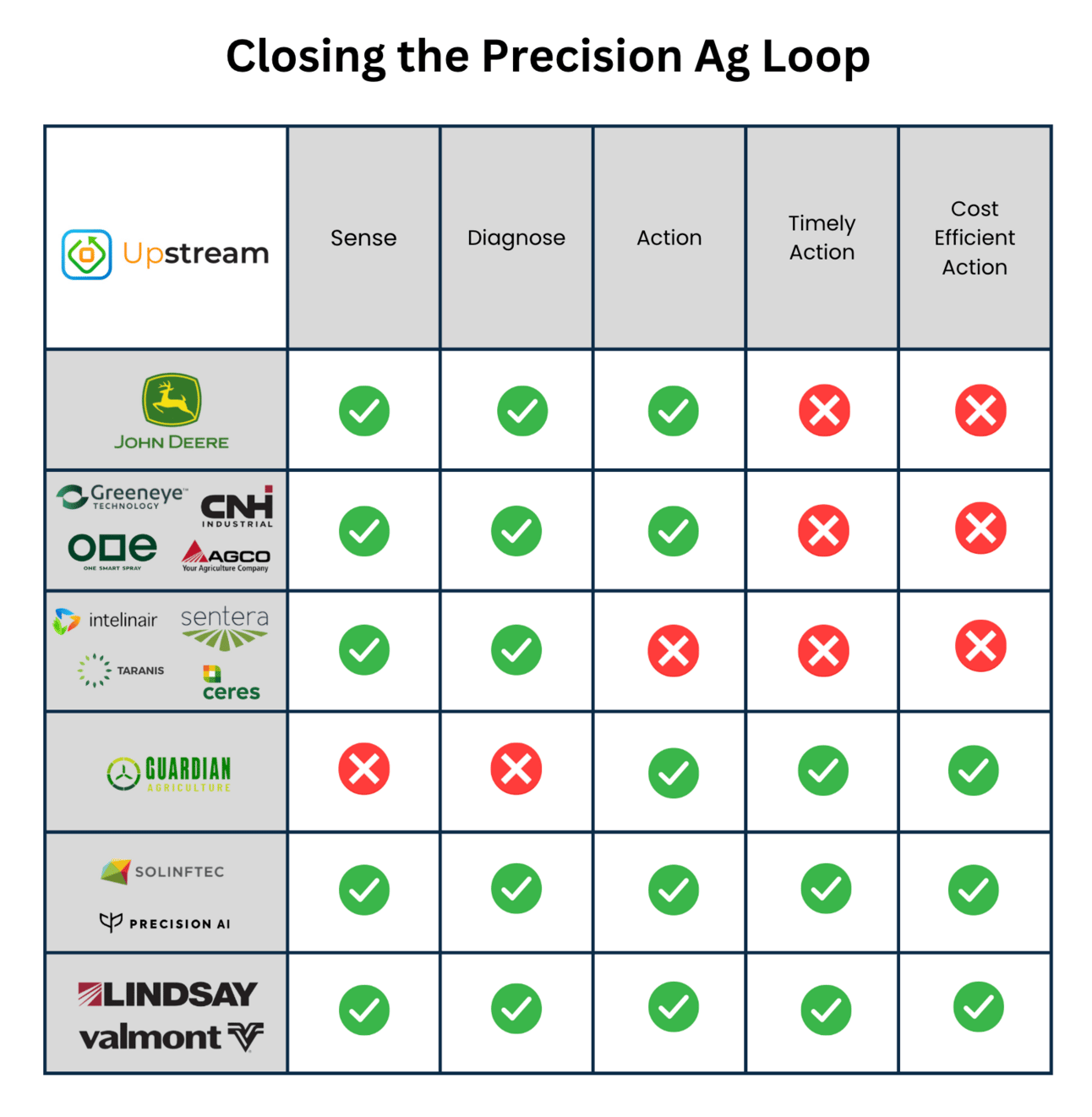

Closed Loops and Precision Ag

Overview

For the past two decades, digital agriculture has over-promised and under-delivered. Much of agtech has focused on sensing (eg: NDVI, drone images, soil sensors) and diagnosing (eg: identifying weeds, plant stand count, disease, or stress), but has stopped short of enabling real-time action to alleviate issues.

The core insight is that agronomic conditions change constantly— weather, insects, disease, nutrient dynamics and a system that checks the field once a week or operates in pre-planned windows cannot truly optimize outcomes.

To close this gap, we must move from episodic sensing and diagnosis to a model where a system closes the sensing to action gap— constantly sensing, diagnosing, and taking action, autonomously, at low cost, and with minimal human labor.

Application

Current practices and agronomic strategies have been optimized around:

- Labor limitations/constraints

- Equipment costs and capabilities

- Fixed application windows

Because of this, most farms follow rigid schedules: one herbicide pass, one fungicide pass, and weekly scouting. But this structure isn’t optimized for what the crop actually needs— it’s optimized around constraints.

By leveraging small, cost-effective, autonomous equipment, there becomes potential to:

- Detect and treat disease or insect outbreaks constantly

- Adjust application plans based on ongoing sensor data

- Apply products only when and where they’re needed

- Reduce wasted inputs and improve ROI

Platforms like Solinftec’s Solix show what this model looks like in practice: solar-powered, autonomous machines that constantly scan the field, run 24/7, and trigger timely action—without adding labor or large depreciation costs.

Takeaway

Digital ag will only deliver its full promise when sensing, diagnosis, and action are tightly integrated and continuously deployed. The next frontier isn’t just smarter tools. It’s systems that think about farming from first principles.

Agribusinesses that design around outcome optimization, rather than labor and equipment constraints, will lead the next wave of agronomic performance and profitability.

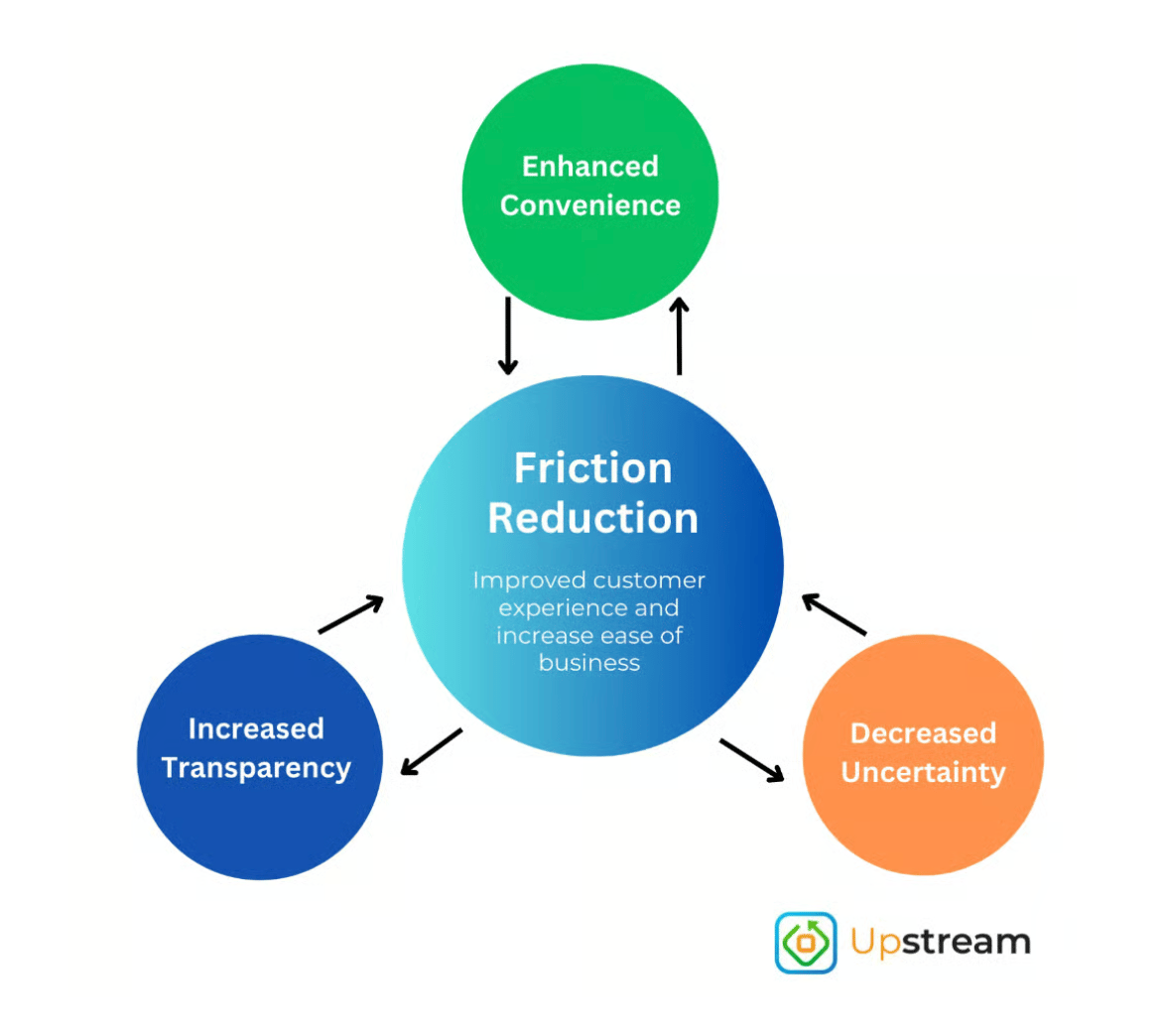

Friction Reduction and Schlep Blindness

Overview

Friction Reduction refers to minimizing points of resistance that make an interaction or task more difficult than it needs to be. It's central to improving a customers experience and is often achieved through thoughtful design, automation, simplification and understanding all of the customer touch points and actions from start to finish.

Schlep Blindness is the failure to notice unpleasant, tedious tasks (“schleps”) because they’ve become normalized. Coined by Paul Graham, it describes how businesses and entrepreneurs often overlook these tasks as innovation opportunities, believing “that’s just the way things are” when they can be improved.

Together, these concepts reinforce a core principle: Many of the best innovations aren’t about inventing something entirely new— they’re about making something less painful by integrating disparate technology, like what Uber did with phones, GPS and thoughtful software design to eliminate the hassles of taxi’s.

Applied to Agribusiness

In agriculture many processes remain full of friction and schleps, both for farmers and agronomists/sales people:

- Paying bills in person, accessing invoices for end of year accounting, waiting on delivery status, filling out financing forms or chasing down custom application confirmations are a few examples.

These aren't just minor annoyances— they consume time, reduce trust, and erode loyalty.

Digital tools have often been narrowly framed around “online purchasing”, but this is just one node in the broader customer journey.

A better framing is: How do we improve every step of the journey before, during, and after the transaction? Or as Lux Capital’s Josh Wolfe likes to ask, “What sucks?”

Uber didn’t win by making a better taxi. They won by enhancing convenience (eg: eliminating a phone call, fumbling for cash), decreasing uncertainty (eg: visual of where your car is, transparent ETA) and reducing friction (simple UI). Agriculture has many of the same types of inefficiencies waiting to be rethought— particularly in ag retail, grain handling, soil sampling and in equipment dealerships looking for service.

Takeaway

A competitive edge doesn’t just come from what you sell— it can come from how simple it is for farmers to work with and buy from you. Look for the clunky, time-consuming parts of the experience that have become “just the way it is”— those are opportunities. Reducing friction across the entire customer journey is one thing that sets great agribusinesses apart.

Strategy Tax

Overview

A strategy tax refers to the trade-offs or internal friction incurred as a result of pursuing a broader strategic direction. It’s not an inefficiency, it’s the cost of making focused, intentional decisions about what a company will prioritize (and what it won’t).

These decisions come with short-term pain, lost sales, added complexity, internal resistance and a host of other potential challenges, but are made because the long-term gain is believed to be worth the cost.

Strategy taxes aren’t mistakes— they’re the price of making purposeful strategic decisions.

Applied to Agribusiness

Strategy taxes show up across the ag value chain when companies shift from legacy models to more focused, differentiated approaches:

Corteva’s Exit of Certain Countries & Products — They gave up low-margin revenue and geographic presence to double down on innovative proprietary chemistry and higher-margin markets which has short term costs and sales losses, but pays off in the form of higher margins and lower overhead in the long run.

Ag Retail Shifting Toward Premium Offerings — A retailer may deprioritize herbicides sales to focus on biologicals, seed treatments, or precision services. That means training new staff, shifting customer messaging, and abandoning short-term sales, including potentially missing out on herbicide bundled offers. However, the aim is to move to higher-margin, less commoditized segments that differentiate and take a more consultative selling approach

Each path involves deciding what not to do and accepting the trade-offs as part of the strategic bet.

Takeaway

If you’re not paying a strategy tax, you probably don’t have a strategy, just a list of activities.

Agribusinesses that succeed in today’s competitive landscape will be the ones willing to let go of good to pursue great, and who align their teams, investments, and focus areas around that vision in spite of a strategy tax.

Contrarian Decisions: Uncertainty is Where the Upside Is

Overview

To outperform in any field, your thinking must be different— yet correct. As Howard Marks puts it, you can’t take the same actions as everyone else and expect superior results. True success comes from making decisions, based off unique insights, that go against the grain and turn out to be right in the long term.

Applied to Agriculture

In agriculture, the most valuable opportunities often aren’t where everyone is looking. If an idea is widely accepted, its upside is usually already priced in— whether that’s in portfolio decisions, pricing strategy, product positioning, or service models. The biggest wins often come from investing early in under appreciated, complex, or unproven areas. This could include new technologies, advisory capabilities, or business models before they’re obvious. This comes with risk, but without the risk you are always going to be capped to mediocre returns and cut throat competition.

Takeaway

If you want to create outperformance, you can’t simply follow where the crowd is going, doing exaclty what others do first. You have to develop insights that others don’t yet see value in and then do the work to bring those to life. The best agribusinesses don’t predict the future— they build it.

This same thing can be talked about with cutting costs— you need to cut them in unique ways, such as vertical integration, finding unique suppliers/supply chains etc.

As Roger Martin has said:

“The best way to spur a race for the bottom is for the competitors in an industry to drive down costs in the same way — and for each to focus on that as its hoped for way to win. That is, they each incur the same set of costs in similar ways. That approach doesn’t produce competitive advantage.”

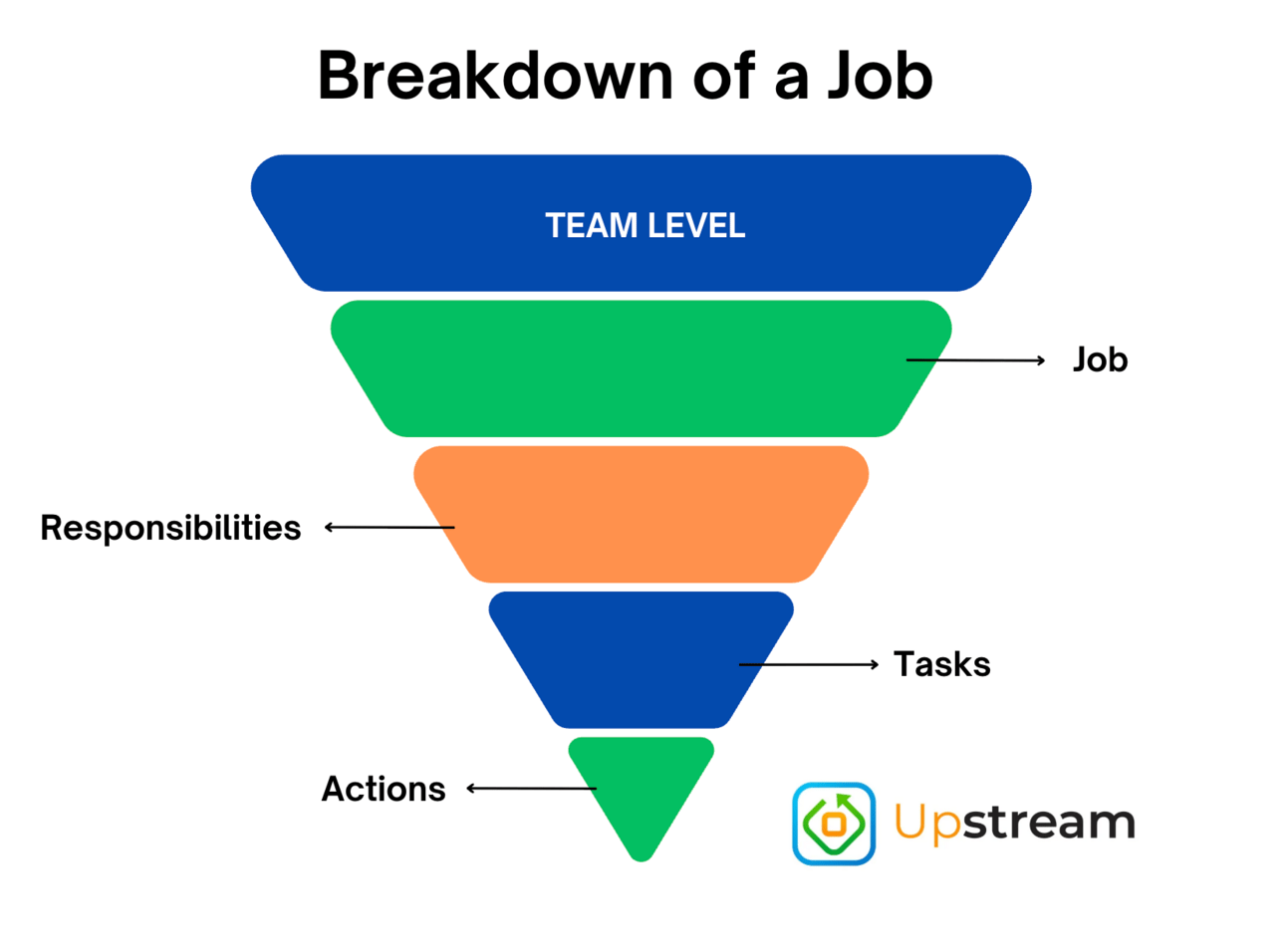

The Lump of Labor and The Job Bundle: Considerations for Artificial Intelligence

Overview

Jobs are not single, static roles—they are bundles of responsibilities, which are fulfilled through tasks, which are executed via actions. For example, a responsibility like “support customers” may include tasks such as writing reports or conducting product evaluations, and actions like taking notes or searching for information.

LLMs don’t replace the entire job, they streamline or automate specific actions (eg: summarizing data, drafting communication) and in some cases tasks. This doesn’t eliminate work, it reshapes it.

That’s where the Lump of Labor Fallacy comes in. It’s the mistaken belief that there’s a fixed amount of work to go around, and if machines do more, people must do less. In reality, increased efficiency lowers costs, creates new demand, and opens space for new responsibilities, tasks, and even entirely new job categories.

Applied to Agriculture

Take the role of an agronomist: it includes responsibilities like product support, problem-solving, and relationship-building. These are executed through tasks like scouting, making input recommendations, or writing field reports and those are made up of actions like driving to a field, typing notes, or searching through resources for information.

LLM are less likely to replace agronomic judgment. But they will:

- Draft communications faster

- Standardize, organize or summarize field data/observations

- Look up product rates faster

- Accelerate research on products and tank mixes

- Help standardize documentation

- Alert to missed opportunities

This reduces time spent on lower-leverage actions and tasks, allowing agronomists to focus more on building relationships, refining recommendations, and delivering value in ways AI can’t.

The broader ag value chain follows the same pattern. Whether in farm management, retail, or manufacturing, automation creates capacity, not displacement. It unlocks new services, roles, and business models that didn’t exist when more time was spent on manual work.

Takeaways

AI will reorganize jobs by compressing the time and cost of repetitive actions and tasks. The professionals and companies that thrive will be those who recognize this shift and reallocate talent to higher-value work.

Jobs to be Done

Overview

Clay Christensen’s Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) framework helps explain why customers choose one solution over another.

The core idea is this:

People don’t buy products or services—they hire them to make progress on a specific task.

A “job” is the underlying progress someone is trying to make, which includes functional, emotional, and social dimensions. When customers “fire” one solution and “hire” another, it’s not just about features or price— it’s because one option helps them achieve their desired outcome better.

Understanding the “job” gives businesses clarity on what their customer truly values—so they can design solutions that align with it.

Application to Agriculture

In agriculture, take the example of a farmer purchasing a crop protection product. They aren’t just “hiring” it to kill weeds in the field— they might be hiring it to:

- Reduce the mental burden of future herbicide efforts (eg: looking for long term residual)

- Signal agronomic credibility to a landlord or to their neighbors

- Fit a specific crop rotation or soil health practice

Understanding the true job being solved for allows ag companies to design tools, services, and messaging that connect on a deeper level— rather than just selling based on features or agronomic specs.

Takeaway

To differentiate and deliver value, stop asking “What are we selling?” and start asking “What job is the farmer or agronomist hiring us to do?” The answer often lies beneath the surface. When you solve for the real job— functional and emotional— you create stickier solutions, stronger relationships, and more resilient business models.

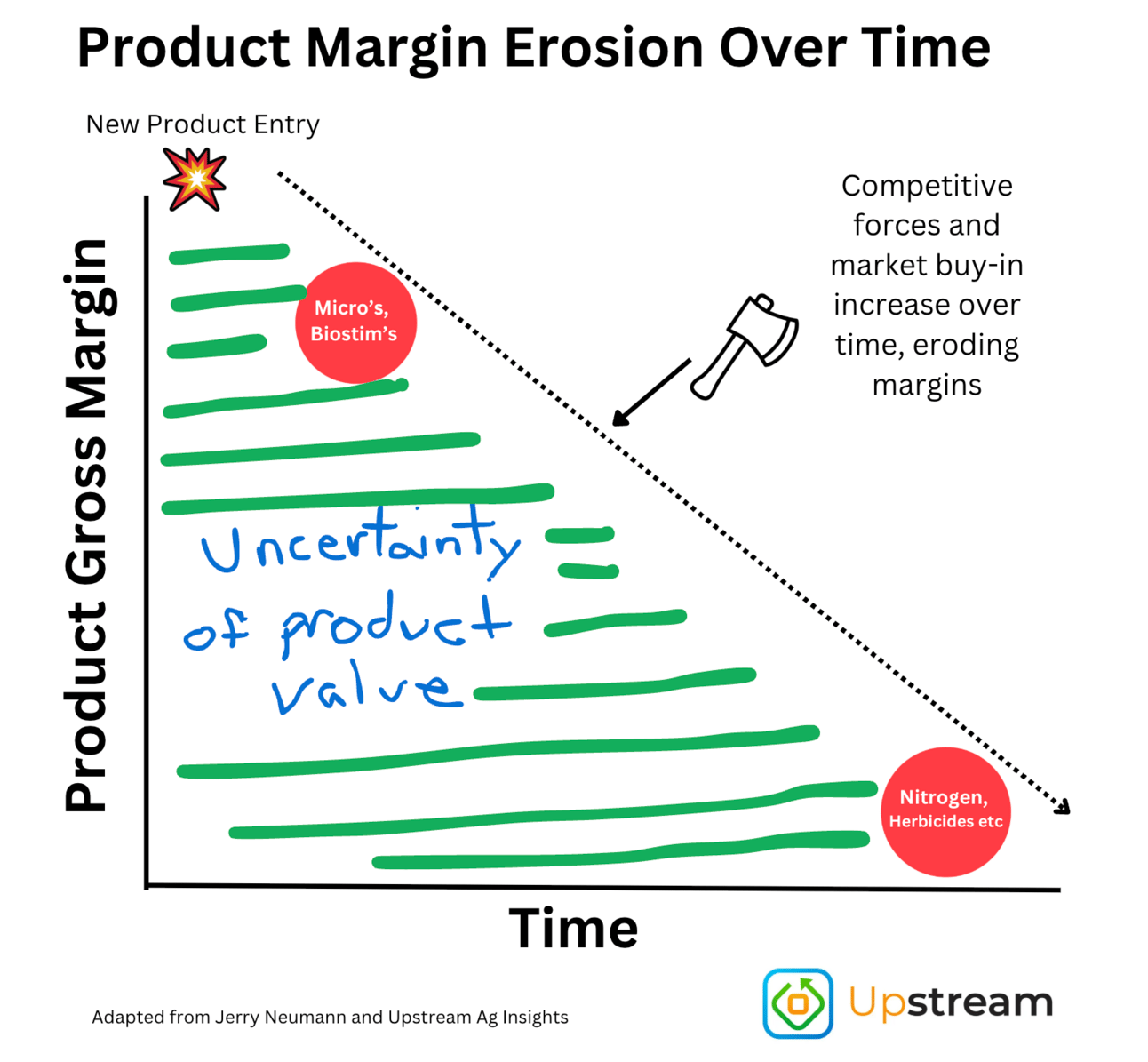

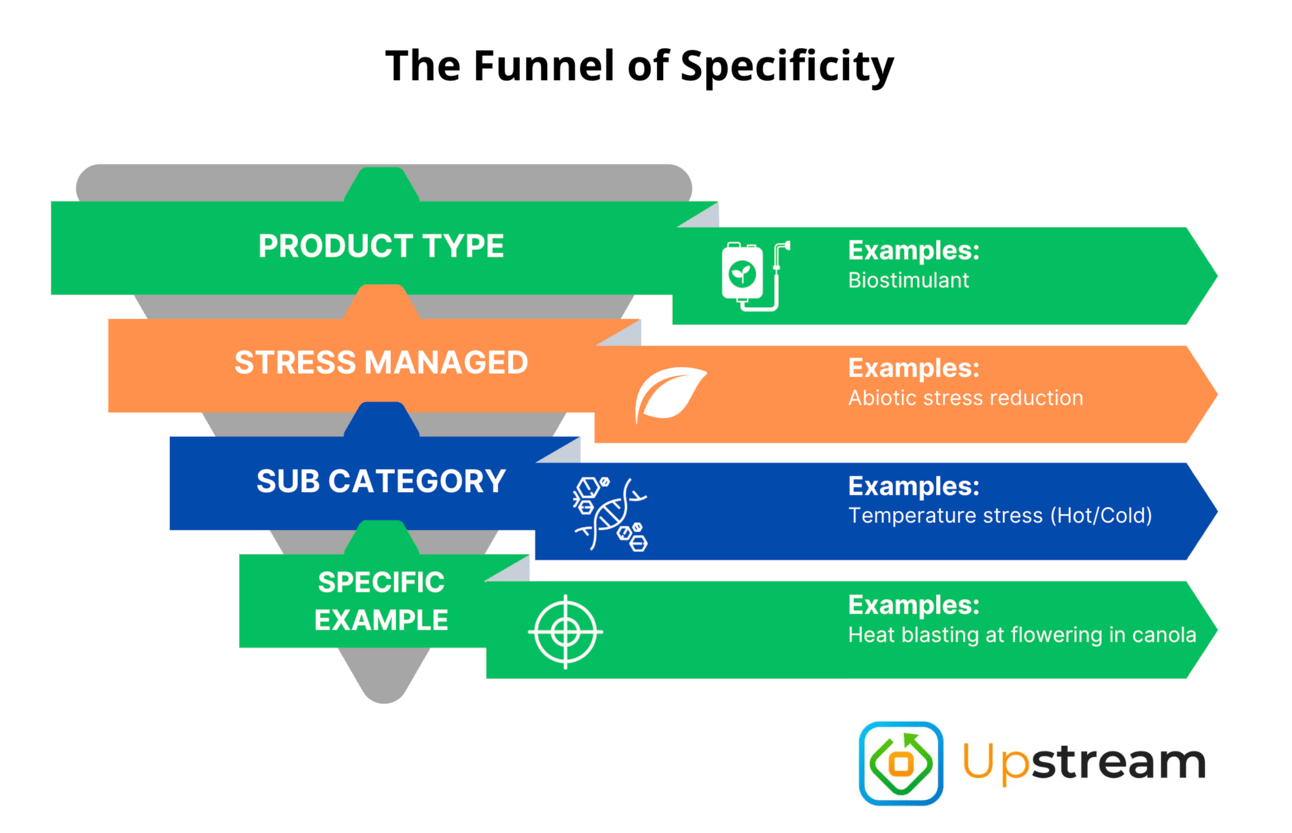

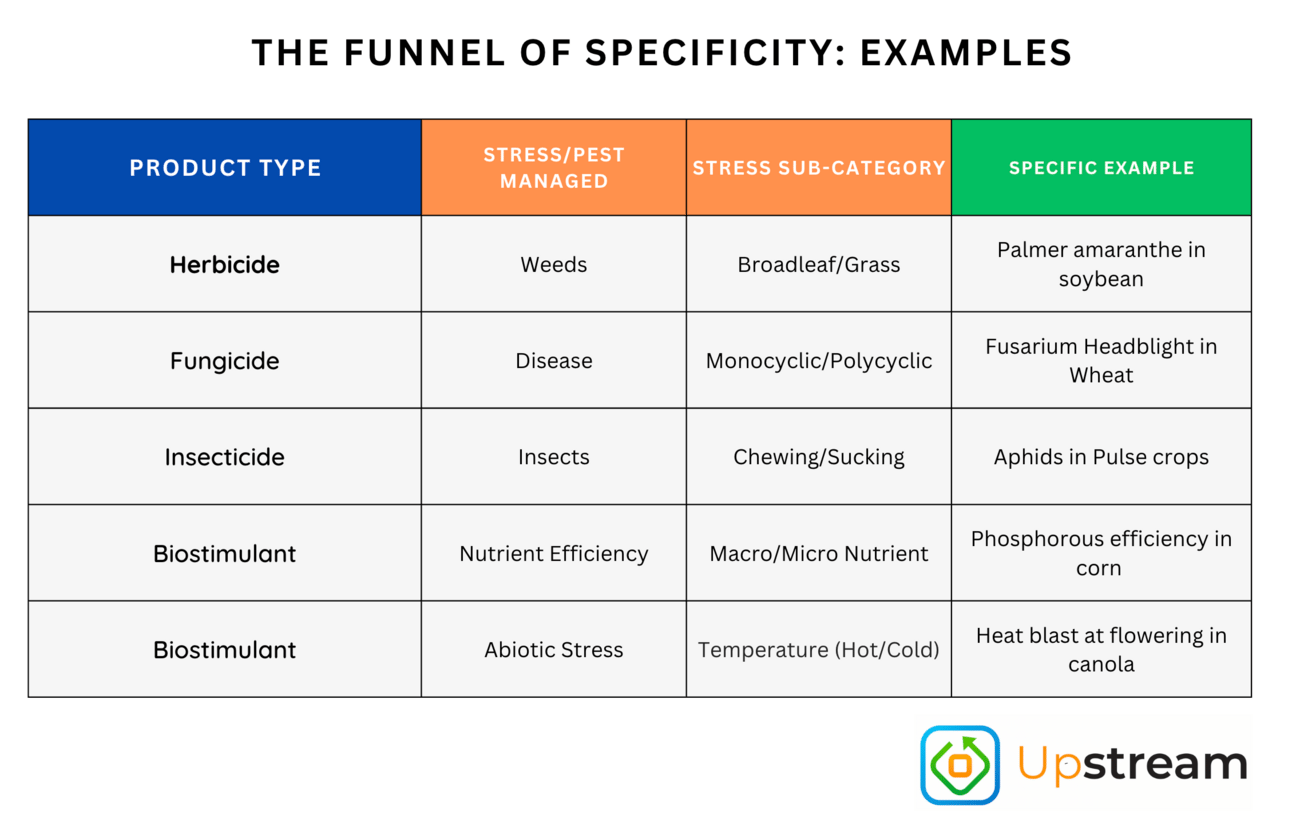

The Sauce Paradox and the Funnel of Specificity

Overview

The Sauce Paradox is the tension between broad applicability and specific market relevance.

It’s tempting to position a product as being good for everything— like Frank’s RedHot Sauce and the famous line “I put that sh*t on everything.” But when a product tries to be everything to everyone, it risks becoming nothing to anyone.

In contrast, BBQ sauce has a focused use case— it’s designed for a specific application, audience, and environment. This approach may seem narrower, but it creates clarity, resonance, and trust.

This ties into the Funnel of Specificity: the deeper you go from broad benefits (“plant health”) to specific and defined crop, condition, and timing— the more compelling and credible your value proposition becomes. It moves from generic claims to specific examples, which drives urgency and association with the problem.

Application to Agriculture

In agriculture, this concept applies acutely to biostimulants, but it’s relevant across many input categories. Most biostimulant positioning sounds like vague wellness advice: “improves plant health,” “enhances resilience,” “manages abiotic stress.” But these claims don’t spark urgency or action.

Contrast this with crop protection. Herbicides aren’t sold as “weed control”—they’re positioned as solutions for specific weeds, in specific crops, at specific times.

The opportunity in biostimulants is to do the same:

- Instead of “stress mitigation,” say “alleviates heat stress in soybeans at R1–R3, decreasing ethylene response and increasing yield by 7% on average when the temperatures rise above 90 degrees F (32 degrees C).

- Instead of “improves nutrient uptake,” say “increases phosphorus uptake and efficiency in soils with a pH above 7.5, leading to increased early season competitiveness and cold tolerance”

This precision helps agronomists and farmers visualize when, where, and why the product fits. It doesn’t limit potential— it gives it a focused entry point. And from there, usage can expand.

Takeaway

Focus drives utilization. The most effective way to position crop input products—especially biostimulants—is to stop trying to be broadly relevant and start being specifically valuable.

Drill down. Anchor your messaging in a specific crop, timing, and agronomic pain point. Doing so gives farmers and agronomists a reason to act—not just to be aware.

The goal isn’t to win every acre at once. It’s to become the default choice in one high-value use case—then build from there.

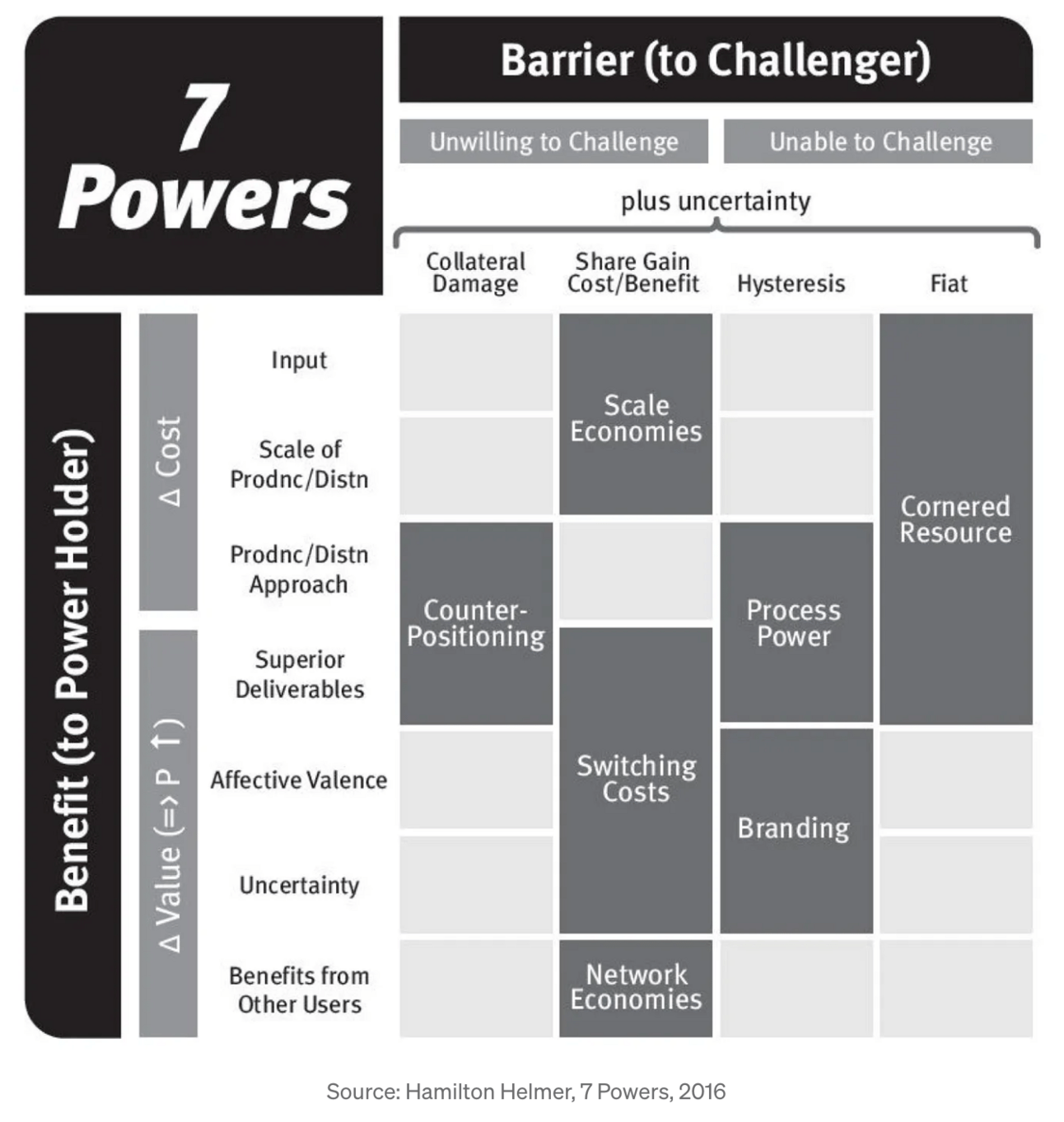

7 Powers by Hamilton Helmer

Overview

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework outlines the sources of durable strategic advantage. The idea is to identify why some companies sustain superior returns over time while others don't. Each “Power” is a distinct mechanism that, if achieved, can create long-term defensibility and profit:

1. Scale Economies – Lower unit costs with increased volume

2. Network Economies – More value created as more users participate

3. Counter Positioning – Doing what incumbents can’t or won’t

4. Switching Costs – Making it costly or inconvenient to change providers

5. Brand – Embedded trust or identity that influences purchasing

6. Cornered Resource – Exclusive access to a valuable asset

7. Process Power – Embedded organizational capabilities that are hard to replicate

Simply having a product is not the same as having Power. Power ensures that advantage is not just temporary—it’s protected and self-reinforcing.

Application to Agriculture

In agriculture, many businesses have strong products or relationships but the aim for any business should be the build up one, or more, of the Powers. The 7 Powers provides a lens to evaluate and think through, as highlighted above, and below includes basic examples.

Scale Economies: Ag retail networks that centralize procurement and logistics gain cost advantages that small independents can’t match, Nutrien is a good example of this.

Network Economies: Digital platforms become more valuable as more users and data are integrated, such as how John Deere Operations Centre continues to grow and gain functionality to drive value to the farmer from the software, but also provide value to John Deere through encouraging more equipment purchases

Counter Positioning: Startups leveraging biologicals or new distribution models can offer what incumbents are structurally hesitant to, such as Meristem Crop Performance.

Switching Costs: Precision ag platforms that store application records, prescriptions, and field history can make switching inconvenient. John Deere Operations Centre is another example here.

Brand: Strong farmer-trusted brands (eg: Pioneer, John Deere) reduce uncertainty and command premium pricing and loyalty.

Cornered Resource: Exclusive access to a talent, IP, data layer, or retail channel can lock in differentiation. In agriculture, this is common speciifcally in crop protection with IP around active ingredients.

Process Power: A manufacturer that has an exclusive process with formulating their products, such as Corteva with the spinosad product line.

Agribusinesses that align their strategies with one or more Powers—and build around them—have a much higher likelihood of sustaining margin and market relevance.

Takeaway

Great products aren’t enough— you need Power. Using Helmer’s framework to assess where your advantage actually comes from, or where a competitors isis highly valuable. Whether you’re a startup, retailer, or multinational, understanding the 7 Powers can be uniquely insightful for future decisions.

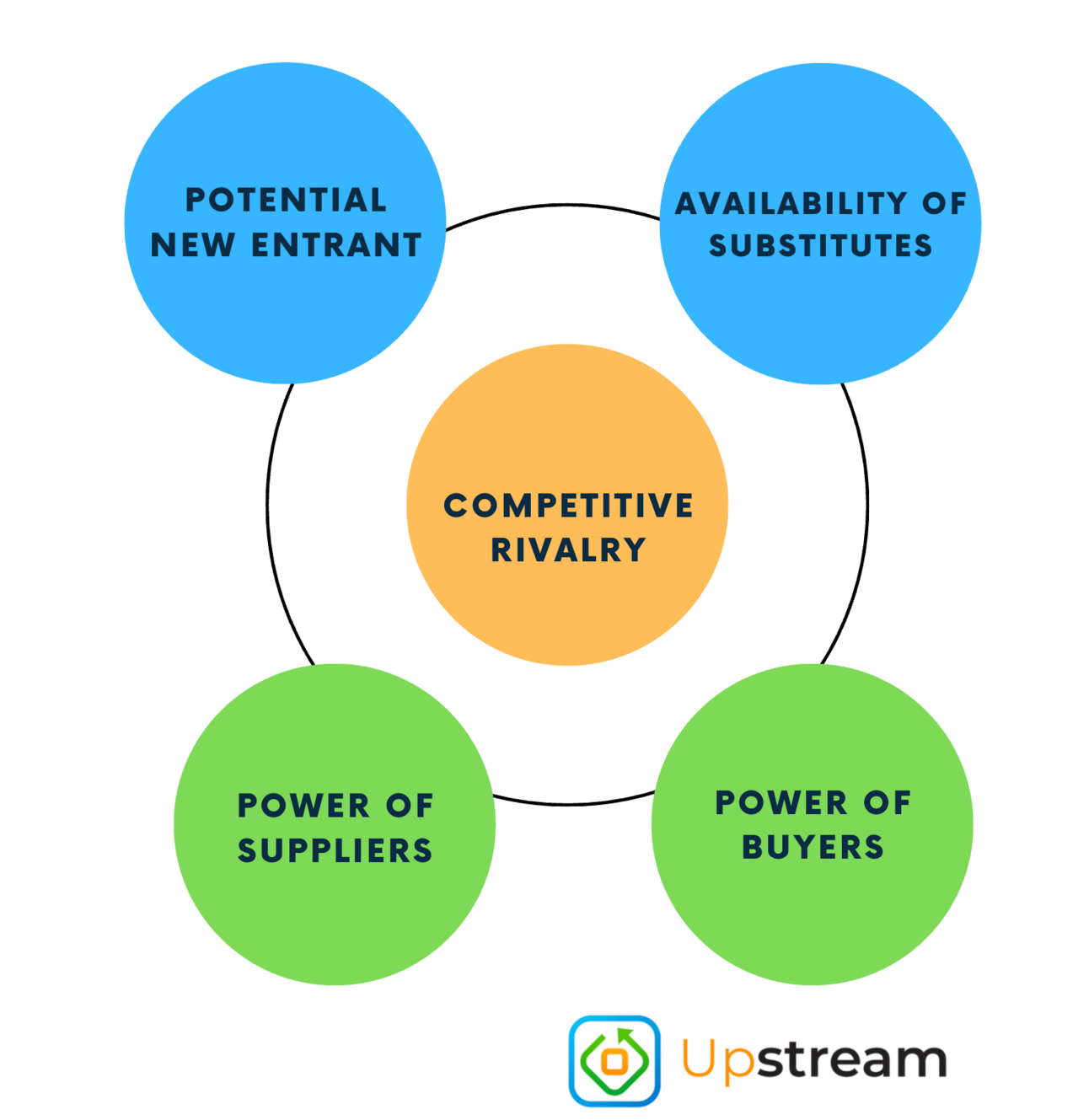

Porter’s Five Forces

Overview

Michael Porter’s Five Forces framework helps explain the competitive pressures that shape an industry’s profitability and the actions of players within that industry. Rather than focusing solely on direct competitors, it assesses the broader dynamics that influence a company’s ability to generate and sustain margins.

The five forces are:

1. Competitive Rivalry – The intensity of competition among existing players

2. Threat of New Entrants – How easy it is for new players to enter the market

3. Threat of Substitutes – The availability of alternative products or solutions

4. Bargaining Power of Suppliers – The influence suppliers have over pricing and terms

5. Bargaining Power of Buyers – The leverage customers have over what they pay

Industries with high force pressure tend to have lower long-term profitability. The goal is to identify where you can mitigate threats or build strategic advantages to improve your position.

Application to Agriculture

Porter’s framework is highly relevant in agriculture, particularly to assess where industry dynamics are shifting and what the implications might be:

1. Competitive Rivalry: Intense in nearly every input category (eg: crop protection, seed, fertilizer), with global manufacturers, generics, and regional players all competing on price and performance.

2. Threat of New Entrants: Lower in traditional inputs due to regulatory and R&D barriers but higher in areas like digital tools, biologicals, or advisory services where capital needs are lower and differentiation is harder to protect.

3. Threat of Substitutes: Biologicals, precision ag, or alternative weed control (eg: light, mechanical) may serve as substitutes to traditional inputs, forcing incumbents to evolve or lose relevance.

4. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Companies sourcing from a few global manufacturers (eg: AI chips, actives for crop protection) may face concentrated supplier power. Conversely, large retailers can negotiate better terms with volume.

5. Bargaining Power of Buyers: Farmers are often price-sensitive and growing in size and sophistication, especially with increasingly transparent pricing, making it difficult for companies to maintain pricing power unless they offer unique value or service differentiation.

Understanding these forces can inform decisions around product strategy, partnerships, pricing, and go-to-market.

Takeaway

Success is about more than a product. It’s about position within the system and value chain, something that was poorly acknowledged early in the industry by tech start-ups. Porter’s Five Forces is useful to map where pressure is coming from and where you have leverage. The best strategies are built by reducing force pressure or turning one of the forces into a competitive advantage.

Innovation Theatre

Overview

Innovation Theatre refers to the appearance of innovation without the substance or impact. It’s when organizations adopt the aesthetics of innovation— hackathons, flashy partnerships, corporate venture arms, innovation titles—without addressing the deeper, structural barriers that prevent real change.

True innovation requires:

- A clear understanding of the problem being solved

- A strategy aligned with business goals

- Commitment to execution

- Cultural and organizational design that supports risk-taking, learning, and iteration

When these are missing, companies often default to copying innovation playbooks from others (usually startups or tech giants) without adapting them to their own context and situation. The result is activity without outcomes and signalling.

Application to Agriculture

In agriculture, Innovation Theatre shows up in many forms:

- Corporate innovation teams isolated from the operational aspects of the business

- Pilot programs run for optics rather than impact

- Incubator participation without a line of sight to move into the business

- Technology investments made for PR or board appeasement, not product-market fit

- Heavy promotion of “being innovative” without measurable outcomes (new revenue, customer success, operational efficiency) aka not aligning the technology with the core business.

A common example: an ag retail business launches a new service using novel technology but doesn’t train staff, tie it to incentives, or integrate it into agronomic workflows. Internally, it’s called “innovation” but on the ground, it’s disconnected and doesn’t drive value to customers or the business.

Contrast that with firms like John Deere, which roll out innovation like See & Spray with deliberate strategy: limited release, direct feedback loops, operational integration, and clear KPIs (eg: recurring revenue goals). Innovation is embedded into the business.

To move beyond theatre, ag companies must start with the real problems of their customers and teams, design solutions with cross-functional alignment, and execute with discipline and patience.

Takeaway

Innovation should not be performative. It should be a process and apart of the culture. If you want results, you have to go beyond the optics. Focus on outcomes, not activities. Align innovation with strategy. Build from the inside-out, not outside-in.

The best agribusiness innovators aren’t chasing headlines, they’re solving meaningful problems with discipline, structure, and a bias for execution. Anything else is theatre.

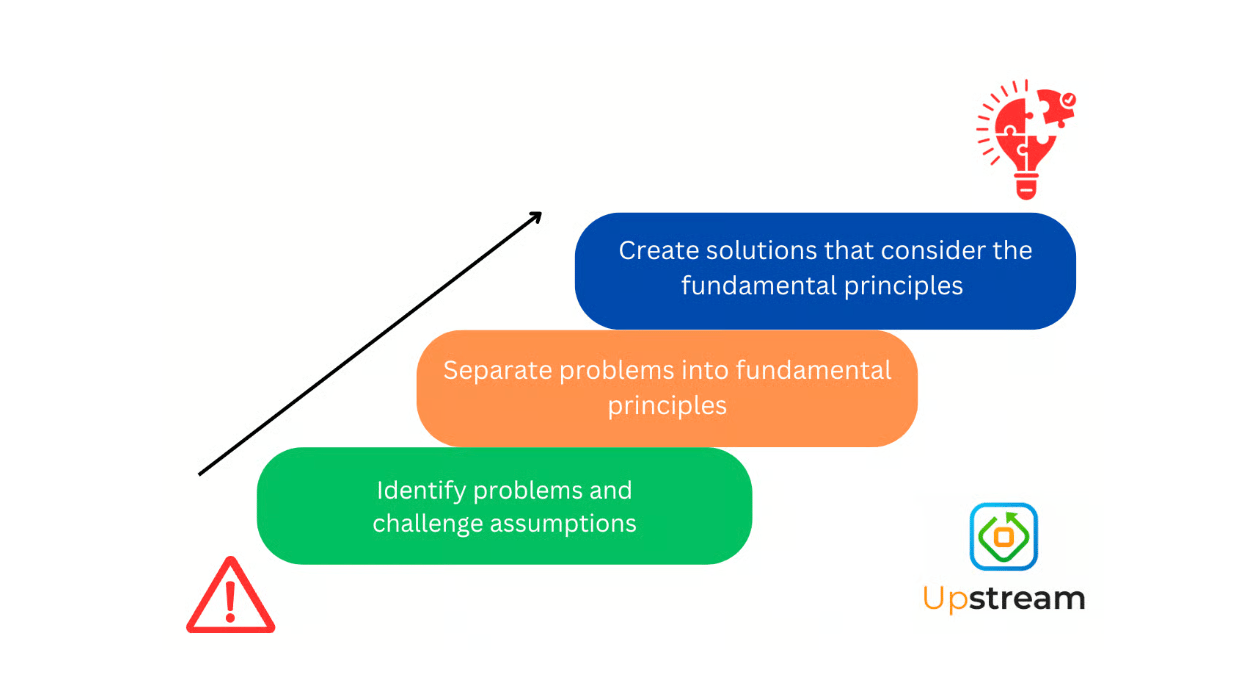

Thinking from First Principles

Overview

First Principles Thinking is a problem-solving approach that involves breaking complex issues down to their most fundamental truths and then reasoning up from there. Rather than relying on analogy (“this is how it’s always done”), first principles thinking asks:

“What do we know for sure to be true?”

“What constraints are real, and which are inherited assumptions?”

This approach enables novel solutions because it frees thinkers from conventional wisdom and industry norms. It’s how Elon Musk reimagined rockets and electric vehicles— not by accepting existing cost structures, but by questioning what was truly fixed and what was merely assumed.

Application to Agriculture

Agribusiness is full of inherited norms:

- Crop inputs must be sold in specific volumes or packaging

- Yield is the primary success metric

- Credit offerings must follow traditional bank frameworks

But when you apply first principles, you can uncover fresh paths:

- Why are input SKUs bundled the way they are? Could pricing or packaging shift to match field-level variability?

- Do all recommendations require in-field visits, or can remote sensing plus local calibration improve scale and speed?

- Is yield the goal— or is profitability, resource efficiency, or resilience more aligned with the grower’s objectives?

- Are input financing decisions based on actual risk— or outdated assumptions about how farms operate?

By stripping down the assumptions, you find areas where innovation is possible.

Takeaways

Challenge assumptions. Start from the fundamentals, not tradition. First principles thinking helps uncover new models, better solutions, and ideas. In an industry full of “that’s the way it’s always been done,” those who break problems down to their essence and build up from there have the biggest opportunity.

The Apps → Infrastructure Cycle

Overview

The Apps → Infrastructure framework, originally articulated by Dani Grant and Nick Grossman of Union Square Ventures, and introduced to me by Bailey Stockdale of Leaf Agriculture, challenges the myth that infrastructure must always come before innovation. Instead, history shows that breakthrough applications create the demand and momentum for infrastructure, not the other way around.

For example, airplanes were created before airports and airport infrastructure were. The airplane is the app, the airport is the infrastructure.

First, a breakout application emerges, solving a problem or introducing a new capability.

That app exposes gaps or bottlenecks prompting a wave of infrastructure development to support scaling, usability, and replication.

That new infrastructure then enables the next generation of applications— more powerful, accessible, and sophisticated than before.

This creates a responsive cycle where each layer builds on the last, accelerating innovation across an ecosystem.

Application to Agriculture

AgTech is now in a new Apps → Infrastructure cycle, built on decades of evolution:

- In the 1980s–2000s, applications like yield mapping and GPS-based record keeping inspired the need for infrastructure: better hardware, connectivity, and software tools (e.g., monitors, sensors, variable rate controllers).

- In the 2010s, apps like Farm Management Systems, agronomy tools, and precision ag software demanded new infrastructure layers: IoT, data standardization, cloud computing, APIs, and scalable farm data pipelines.

- Now, in the 2020s, new applications such as digital platforms, ag fintech, autonomous equipment, are being built on top of the existing infrastructure and unlocking value.

Crucially, companies like Leaf are building purpose-built ag infrastructure to solve foundational problems such as secure data access, field boundary management, file standardization, that every new app struggles with. These companies are doing for ag what AWS did for general web apps: abstracting away complexity so developers can focus on core value.

This cycle explains why some ideas like drones failed a decade ago but are now looking more promising. The infrastructure finally exists to make them viable, scalable, and user-friendly.

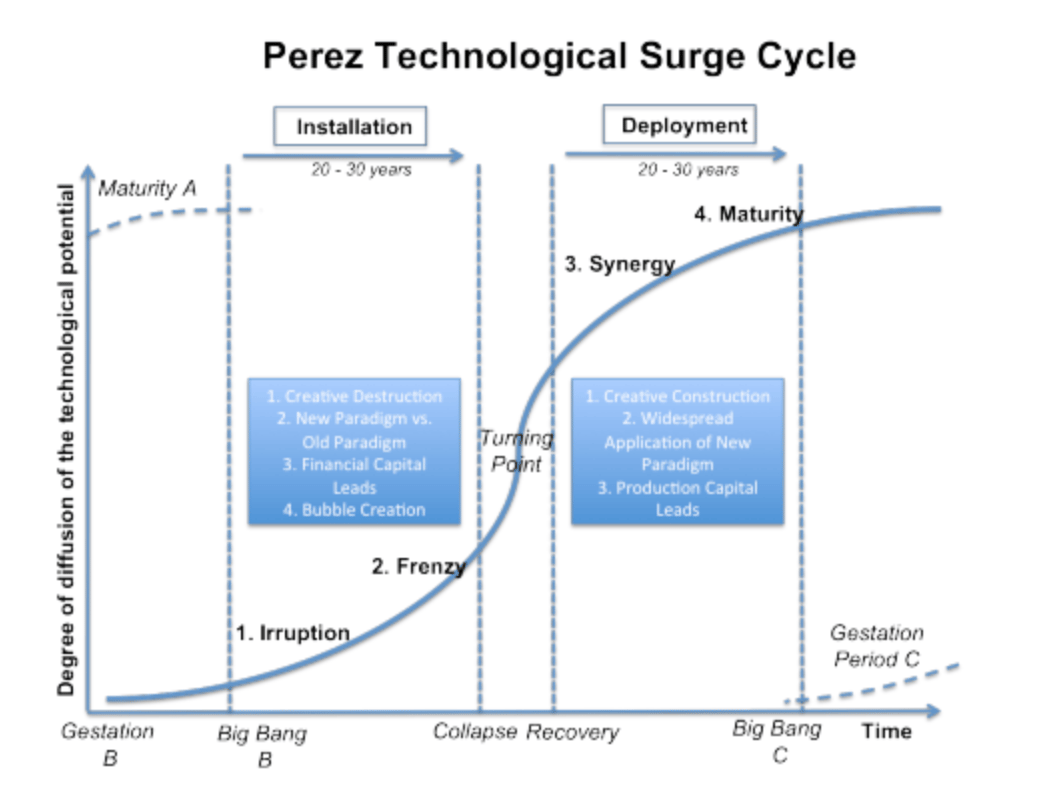

Source: Technological Revolution and Financial Capital by Carlotta Perez

Overview

Related to apps and infrastructure, Carlota Perez has written extensively on technological revolutions and argues that every major technological revolution follows a repeatable pattern made up of five phases that she breaks out into Installation and Deployment phases: Irruption, Frenzy, Turning Point, Synergy, and Maturity.

Each cycle begins with a breakthrough innovation (irruption), which attracts speculative capital and leads to over investment (frenzy). This often results in a correction or crash (turning point), followed by broad adoption and productivity gains (synergy), before eventually reaching saturation (maturity).

The core insight: technology adoption is not linear, it follows cycles shaped by the interplay of innovation, finance, policy, and production. It’s notable to think through these concepts as it pertains to agriculture and when technology is in a place to go from the infrastructure to deployment phase.

Takeaway

The technologies creating real value today were planted in earlier cycles, and those investing in infrastructure, integration, and execution now are best positioned to lead in the synergy phase.

Avoid chasing hype. Focus on building for the deployment era: systems that solve real problems, scale with the existing ag infrastructure, and align with how the industry actually operates.

Trapped Value

Overview

Trapped Value refers to value that exists in a system but isn’t being captured, monetized, or unlocked due to structural, organizational, or technological barriers. Geoffrey Moore, author of Crossing the Chasm, introduced this concept to explain why companies or industries may have latent potential that remains unexploited.

Common causes of trapped value include:

- Siloed data

- Disconnected processes

- Misaligned incentives

- Legacy systems or workflows

- Poor user adoption or integration

- Idle assets

New technology and business models often succeed not by creating entirely new value, but by unlocking trapped value that already exists in a system, making it visible, accessible, or monetizable.

Application to Agriculture

Agriculture is full of trapped value:

- Data trapped on USB sticks, machines, or isolated systems that could inform better decisions but isn't being used.

- Inefficiencies in rebate tracking, agronomic recommendations, or inventory management that cost time and margin.

- Information asymmetry between manufacturers, retailers, and farmers, which limits the effectiveness of product positioning or planning.

- Idle pieces of equipment or storage facilities.

Takeaways

Innovation isn’t always about creating new value, it’s about unlocking what’s already there. Trapped value exists everywhere— in processes, data, assets and workflows. Companies and professionals that identify where that value is stuck and build the systems, tools, or services to release it find opportunities.

Weak Link vs. Strong Link Problems

This concept is rooted in decision theory and distinguishes between two types of problems:

1. Weak Link Problems: The overall outcome is limited by the weakest contributor. Think of a chain— strength is determined by its weakest link. Improving performance of the weakest link means lifting the entire strength of the chain.

2. Strong Link Problems: The outcome is determined by the best performer. Think of venture capital or elite sports, returns or results are driven by outliers. The key is to amplify the best.

Understanding whether you're facing a weak link or strong link problem changes how you invest, structure teams, and make strategic decisions.

Application to Agriculture

Agriculture is full of weak link dynamics, and biological crop inputs are a prime example.

In the biologicals space, a small number of poor-quality products or bad actors can damage the reputation of the entire category. When farmers or advisors encounter one ineffective or overstated product, they often generalize: “biologicals don’t work.” This is a textbook weak link issue, the lowest performers drag down the whole system. Compounding the problem is the lack of regulation. Unlike synthetic crop protection, which is tightly regulated, most biostimulants and biologicals face only light or voluntary oversight. That allows low-quality products into the market, creating noise and confusion, making it harder for good products to earn trust or gain traction.

This is further intensified by the fact that crop production itself is a weak link system, Leibig’s Law reminds us that yields are constrained by the most limiting factor. Applying a weak biological in a yield-limiting environment amplifies the risk of failure.

Eliminating the lowest-performing products through higher standards, better screening, and possibly tighter gatekeeping (whether via regulation or channel accountability) would lift the baseline and improve outcomes for everyone involved—especially farmers.

The challenge is knowing when to focus on consistency and reliability (weak link) vs. breakthrough performance and upside (strong link).

Takeaway

Know which problem you're solving.

If it’s a weak link problem, focus on raising the floor: better training, system reliability, and addressing the most common points of failure.

If it’s a strong link problem, invest in the top performers, high-upside innovation, and scaling what works best.

Misdiagnosing the problem leads to wasted effort.

Eroom’s Law in Crop Protection

Overview

Eroom’s Law (Moore’s Law spelled backward) describes the declining R&D efficiency in drug discovery, where the cost and time to bring a new drug to market have increased, despite technological advancements. The cost of development has doubled roughly every nine years, while success rates have dropped.

Key drivers include:

- Rising regulatory demands

- Incremental product differentiation (“Better than the Beatles” problem)

- Sunk cost bias and over-resourcing

- Over reliance on brute force scientific methods

- The decline of low-hanging fruit

It challenges the assumption that more technology and spending naturally lead to more innovation. Instead, it reveals how complex systems and rigid structures can cause innovation slowdown despite technical progress.

Applied to Agriculture

The same dynamics are playing out in crop protection:

- R&D costs and timelines have grown significantly over the last two decades. Developing a new active ingredient now exceeds $300 million and can take more than 10 years.

- Fewer actives are coming to market, despite increasing R&D budgets.

- Regulatory hurdles (particularly in the EU) and sustainability requirements are slowing progress further.

- Lots of new innovation is coming from outside the traditional manufacturers—startups, not internal pipelines.

- Brute-force discovery models are giving way to platform-based approaches, such as AI-enabled discovery, combinatorial libraries, and target-based design.

In parallel, biologicals are receiving greater attention, due in part to lower development costs, faster go-to-market timelines, and the potential to circumvent some of the regulatory and R&D burdens plaguing synthetic chemistry.

Takeaway

Crop protection is experiencing an Eroom’s Law dynamic— rising R&D costs, longer development timelines, and fewer breakthrough products, despite better technology. Traditional discovery models are no longer efficient, and future innovation will increasingly come from external partnerships and platform-based startups. To stay competitive, companies must shift from relying solely on internal pipelines to building and accessing broader innovation ecosystems.

Rugged Landscapes

Overview

The Rugged Landscapes framework comes from evolutionary biology and was adapted for strategy by Daniel Levinthal. It visualizes the strategic environment as a three-dimensional terrain filled with multiple peaks and valleys. Each point on the landscape represents a different configuration of organizational decisions and capabilities, with elevation representing the level of "fitness" (eg: performance or competitive success).

In this metaphor:

- Peaks represent successful strategic configurations.

- Valleys represent underperforming or misaligned ones.

- Organizations aim to climb to the highest peak available, but due to interdependencies between decisions and capabilities, making progress is complex and nonlinear.

The landscape itself is dynamic, not static— external forces (technology, regulation, consumer preferences) can shift the terrain under your feet.

Applied to Agriculture

Agribusiness operates in a rugged landscape defined by biological constraints, regulatory forces, and market complexity. Strategy in this context is not about being the largest player—it’s about identifying the right peak to climb and aligning the business to do so.

- A company may aim to lead in biological crop inputs, but doing so requires alignment across R&D, distribution, regulatory navigation, and farmer education—any misalignment can leave the business stuck in a valley.

- Equipment manufacturers face trade-offs: a multi-brand approach requires different capabilities than a vertically integrated single-brand model. AGCO’s evolution reflects climbing a different hill than John Deere.

Because of interdependencies (eg: tech stack decisions affecting dealer success, regulatory pressures influencing product roadmaps), one move can enhance or weaken another. Strategic missteps can mean falling into a valley with no clear path back.

In short, no two agribusinesses will follow the same path, and not all paths lead to the same peak.

Takeaway

Strategy is not a linear march to the top, it’s a complex journey through a complex terrain. Success comes from making focused, aligned decisions based on where you want to win, then committing to the climb. Misalignment or chasing too many opportunities can leave you stranded. In a rugged agricultural market, clarity of vision, alignment of capabilities, and adaptability are what separate peak performers from those stuck in the valleys.

Value Chain Mapping & Modularity

Note: This can be adjusted for equipment, insurance etc. It also can go back upstream further beyond input manufacturer to look at formulation technology, inerts, active ingredient suppliers etc.

Overview

Value chain mapping is the process of visually laying out all the key participants and functions involved in the flow of goods, services, and dollars within an industry — from raw material to end user. It highlights where value is created, captured, and transferred, and it helps identify where margin pools concentrate or erode. Can be useful in conjunction with other frameworks, like Porters Five Forces.

A component of this is understanding modularity: which parts of the chain are standardized, easily replaced, or commoditized and which are integration points or points where differentiation, pricing power, and strategic leverage live.

Mapping also makes clear where dollars enter the system (eg: government programs, consumer spend, farmer investment), how risk is distributed, and where new entrants or technologies might shift the flow of value upstream or downstream.

Application to Agriculture

In agriculture, the value chain spans from input manufacturers (seeds, chemicals, equipment) through retailers, farmers, processors, and consumer-facing food brands. Mapping this chain helps agribusinesses and innovators:

- See where margins pool (eg: proprietary genetics, high-tech equipment, brand-name food products)

- Understand which segments are modular and low-margin (eg: basic distribution, generic inputs)

- Spot where new technologies might reconfigure where value accrues

- Recognize friction points or choke points that might be prime targets for innovation or control

For example, new technology introduced into the value chain— such as InnerPlant’s signalling trait, may create new value or shift value away from traditional crop protection products.

Takeaway

If you don’t understand how value flows through your industry including who makes what margin, where differentiation happens, and where it’s collapsing, then your strategic decisions risk being misinformed. Value chain mapping is essential for identifying control points, threats of commoditization, and opportunities to capture or shift margin.

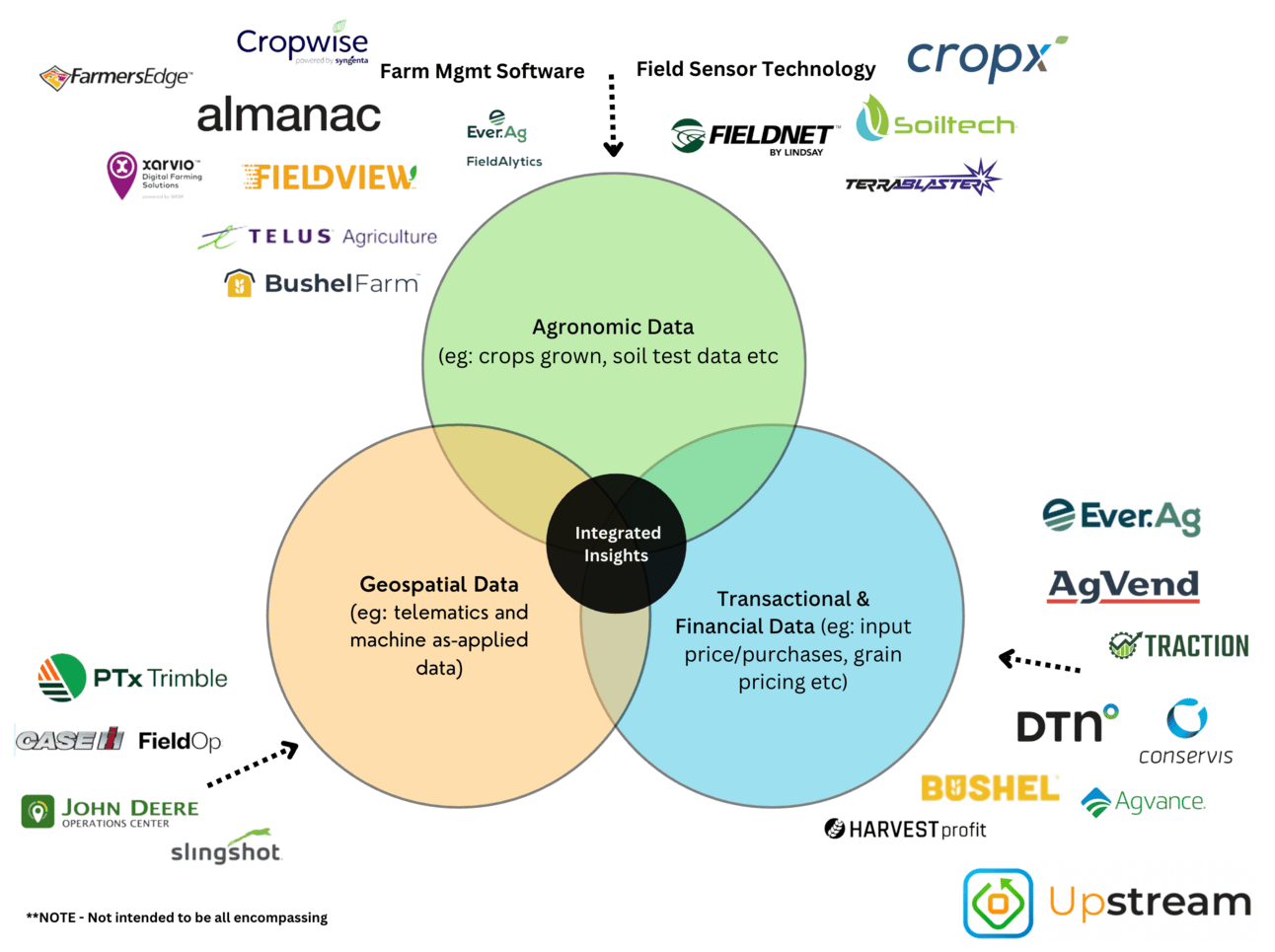

Integrated Insights

Overview

Data convergence refers to the integration of distinct but complementary data types, in this case: agronomic, transactional, and geospatial data into a unified spot. Each type of data tells part of the story:

- Agronomic data (eg: crop scouting, tissue tests, application records) reveals biological and management performance.

- Transactional data (eg: invoices, rebates, input purchases) shows economic decisions and costs.

- Geospatial data (eg: satellite imagery, field boundaries, yield maps) ties everything to a specific place and time.

When these data streams converge, they unlock compounded insight: things like field-level profitability, or cost-to-serve metrics by acre or crop. The shift is to move all of these types of data together better.

Application to Agriculture

Historically, most ag software has siloed these data types. For example:

- Climate FieldView, Fieldalytics, Bushel Farm capture geospatial and agronomic data.

- AgVend, Merchant Ag, Bushel manages transactional and customer data.

By integrating these of data, farmers and support teams can start to see real-time financial and agronomic performance together, rather than separately. This convergence builds a more complete picture of each acre, from what was applied, to how much it cost, to how well it performed, informing decisions, and improving outcomes.

Takeaway

The future of farm software isn’t in siloed tools, it’s in systems that integrate what happened, where it happened, and what it cost. Data convergence is the foundation for unlocking actionable, acre-specific insights that drive better decisions, tighter advisory relationships, and long-term value creation.

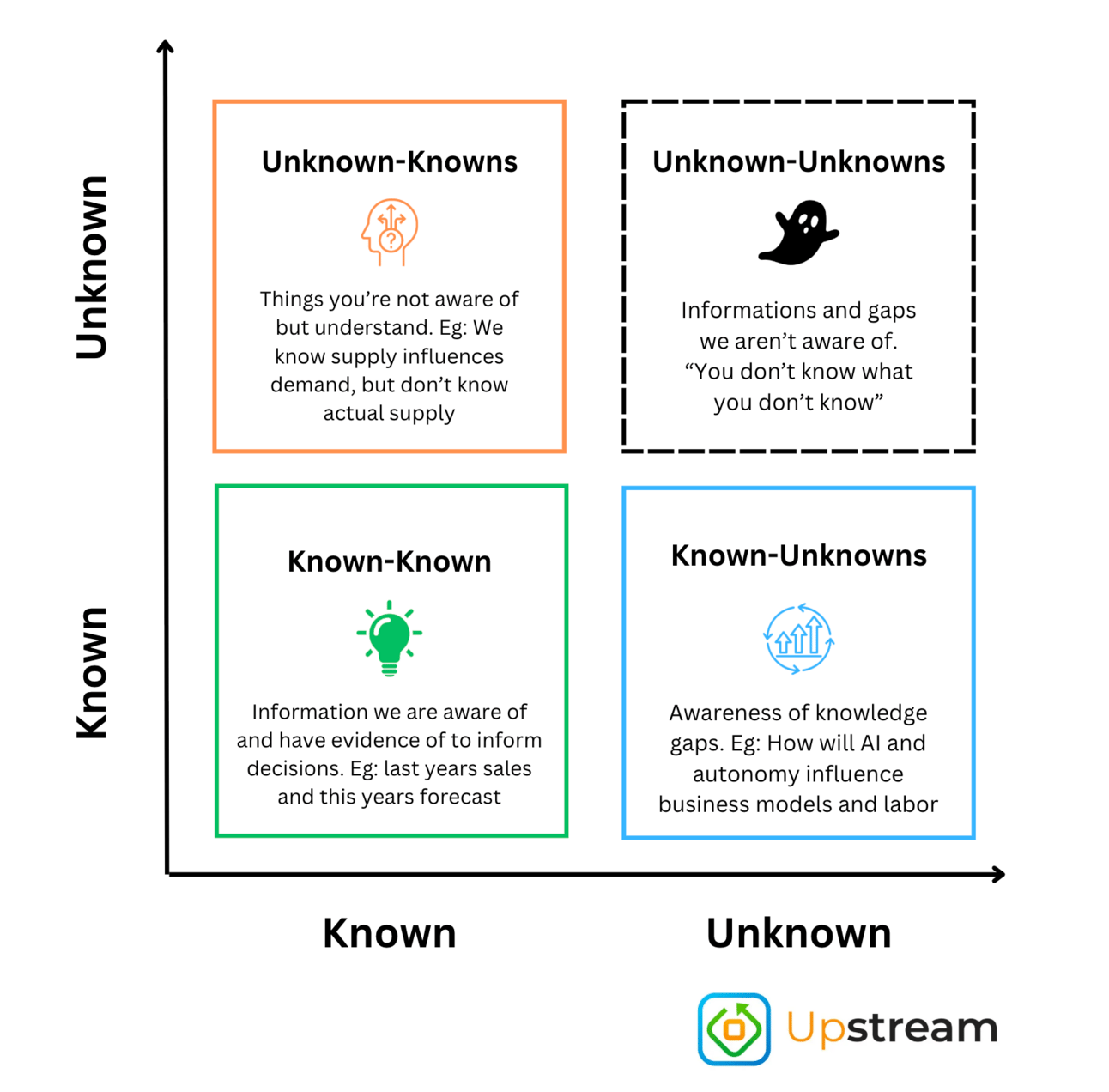

Unknown Unknowns Framework

Overview

Originally popularized by Donald Rumsfeld and later expanded in risk and strategy circles, the “Knowns and Unknowns” 2x2 framework helps organizations understand what they know, what they don’t know, and the implications of each.

The four quadrants are:

1. Known Knowns – Things you understand and are aware of (eg: your current customer base or pricing strategy).

2. Known Unknowns – Things you are aware you don’t understand but can investigate (eg: how a new regulation will impact your margin).

3. Unknown Knowns – Things you should know, but aren’t consciously aware of (eg: institutional knowledge not being utilized).

4. Unknown Unknowns – Things you don’t know that you don’t know. These are the most dangerous and unpredictable risks or opportunities (eg: a sudden geopolitical shock, or a disruptive new entrant from outside agriculture).

Application to Agriculture

In agribusiness, many decisions are made under uncertainty — weather, biological response, regulatory shifts, geopolitical impacts, or technology adoption rates.

Known Knowns might include your herbicide pricing or seed product portfolio.

Known Unknowns could be how new biologicals will perform across soil types.

Unknown Knowns are often buried in legacy agronomic data or underused CRM platforms — things your organization has but isn't acting on.

Unknown Unknowns emerge from black swan events: supply chain shocks, disruptive agtech business models, or new buyer behavior you haven’t anticipated.

The framework reminds agribusiness professionals that strategic planning isn't just about managing the obvious, it’s about recognizing where uncertainty exists and building resilience and optionality into your decisions.

Takeaway

In an increasingly volatile ag landscape, competitive advantage goes to the firms that not only manage the knowns, but actively build processes to surface unknowns, reduce blind spots, and stay adaptive. Scenario planning, cross-functional data integration, and front-line feedback loops help reduce exposure to “unknown unknowns” before they become costly realities.

Ergodicity

Overview

Ergodicity is a concept from probability theory and systems thinking that distinguishes between what happens on average across many individuals versus what happens to one individual over time.

In an ergodic system, time and group averages are interchangeable. For example, if everyone flips a coin 100 times, the average result is the same as one person flipping a coin 100 times. Optimization makes sense in such systems.

In a non-ergodic system, the outcomes for an individual over time are not reflected in the group average. A single catastrophic event (e.g., bankruptcy, crop failure) can eliminate future participation. In these systems, survival—not optimization—is the rational strategy.

Nassim Taleb popularized the idea to explain why people with “skin in the game” often behave more conservatively than abstract models would suggest. One irreversible loss nullifies a thousand small gains.

Application to Agriculture

Farming is a textbook example of a non-ergodic system:

- A farmer doesn’t get to farm 1,000 hypothetical fields to “average out” the risk. They have one season, one farm, and one financial life.

- If one poorly understood product wipes out a field, the average ROI of other products is meaningless.

- The bar for trying new technologies—whether biologicals, digital tools, or equipment, is high not because of laziness or conservatism, but because failure in a single instance can ruin a farm that has previously been around for decades.

- Agronomists and ag retailers operate in a similarly non-ergodic world. One bad recommendation can erode years of credibility and sales.

This non-ergodic reality is why farmers prioritize reliability over optimization, and why new products must overcome perceived and real risk, not just offer theoretical upside.

Takeaway

Agriculture operates in a non-ergodic environment where trust and reliability trump optimization. To succeed, sellers of new products or technologies must reduce perceived downside risk through validation, transparency, and demonstrating operational fit, not just promise higher returns. Survival-focused decision-making is rational in this context, and sales or marketing teams must align with that mindset.

One-Way vs. Two-Way Door Decisions

Overview

Jeff Bezos introduced the idea that most business decisions fall into two categories:

- One-Way Doors: These are irreversible or very hard to reverse. Once you walk through, you can’t easily go back. These require deliberation, data, and senior oversight. Examples: a major acquisition, shutting down a product line, or entering a new geography.

- Two-Way Doors: These are reversible. If you go through and it doesn't work out, you can back out or change direction. These should be made quickly, often by frontline teams with less process overhead.

The key insight: Most decisions in business are actually Two-Way Doors—but companies treat them like One-Way Doors, slowing progress unnecessarily.

Application to Agriculture

In agribusiness there’s a tendency to treat most decisions with a high degree of caution. But not every decision should be viewed through that lens.

One-Way Door examples in ag: Committing to a proprietary seed trait license for 10 years, acquiring a tech company, investing in a new production facility.

Two-Way Door examples in ag: Trialing a new biostimulant on 200 acres, piloting a new digital advisory tool, adjusting sales incentives for a single year, testing a new retail training program.

Too often, relatively low-risk changes (e.g. adjusting marketing messaging, piloting a pricing strategy, trialing software integrations) are slowed down because they’re treated like One-Way decisions.

This hurts learning speed, reduces adaptability, and delays value creation.

Takeaway

Misclassifying Two-Way decisions as One-Way is a hidden drag on speed, innovation, and competitiveness in agribusiness. Leaders should focus on reserving the heavy processes for truly irreversible calls while empowering team for the two-way decisions.

The Barbell

The Barbell Effect is a concept that describes how markets polarize over time, squeezing out the middle. In business, this means value and growth increasingly accrue at the two extremes:

- High-end / premium / specialized

- Low-cost / commodity / scaled

What gets hollowed out is the middle. The businesses that are neither the cheapest nor the best, often offering undifferentiated products or services with moderate pricing. These companies face the highest pressure, as they’re too expensive to compete on price and too generic to justify premium margins.

The Barbell Effect shows up as bifurcation: customer preferences and market dynamics shift to favor either extreme, leaving the “safe” middle increasingly untenable.

Application to Agriculture: Ag Retail

In ag retail, the Barbell Effect is already playing out and accelerating:

- On one side: Low-cost/volume players (eg: large independents, co-ops, digital-first platforms) who compete aggressively on price, logistics, and scale. They strip away services and use technology to drive efficiency and margin.

- On the other: High-service, specialized retailers offering trusted agronomy, premium advisory services, customized programs, or niche biological/tech product offerings. They build deep relationships and justify higher pricing through technical expertise and outcomes.

In the middle: traditional retailers without deep technical differentiation and without meaningful cost advantages. These players are struggling. Their margins are compressed by upstream manufacturers, eroded by downstream digital entrants, and challenged by rising expectations from farmers who either want lowest price or highest value, not moderate versions of both.

This middle layer often suffers from legacy systems, outdated incentives, lack of clear positioning, and internal resistance to change. They're too slow to automate, too generic to command a premium, and too costly to win on price.

Takeaway

The agribusiness in the middle is under pressure. Succeeding in this environment requires picking a side: scale or specialization.

If you can’t out-service, out-specialize, or out-advise— you must out-scale and out-operate.

If you can’t out-price, out-logistics, or out-tech— you must become indispensable through agronomic and relationship excellence.

Trying to be all things to all customers in the middle is a strategic dead end. The barbell is real. Choose your side— or risk being squeezed out.

Control: Influencing the Market vs. Letting the Market Influence You

Overview

In business, there's a critical difference between reacting to the market and shaping it. Many companies operate with the assumption that customer behavior, demand, and budgets are fixed. But in practice, perceptions influence behavior and those perceptions can be shaped. Strategic positioning, communication, and education can turn passive buyers into active customers, even in down markets. Companies that influence how the market sees value tend to outperform those that wait for conditions to improve.

Application to Agriculture

Agribusinesses often default to a reactive stance. When crop prices fall or interest rates rise, they assume farmers will cut spending across the board. But not all companies respond that way. Some continue to educate, market, and proactively sell—framing their product as critical, not optional. This leads to growth, even in flat or declining market conditions. Others cut back on outreach and are surprised when sales shrink. The market isn’t monolithic—farmer perceptions and decisions are influenced by how products are positioned and supported.

Takeaway

Market demand is not fixed— it’s influenced. Success comes from actively shaping customer perception, not waiting for conditions to shift. Companies that understand this don’t just respond to the market, they move it.

Jevons Paradox

Overview

Jevons Paradox describes a counterintuitive phenomenon: as technology increases the efficiency with which a resource is used, the overall consumption of that resource may actually increase—rather than decrease.

First described by economist William Stanley Jevons in 1865 in the context of coal consumption, he observed that as steam engines became more fuel-efficient, total coal use increased because lower operating costs expanded their use across more industries.

This paradox challenges the assumption that efficiency alone leads to conservation. In many systems, improved efficiency reduces costs, which can stimulate greater usage, expanding demand and eroding the efficiency gains.

Applied to Agriculture

Precision agriculture technologies like variable rate fertilizer, targeted herbicide application, or optimized irrigation are often heralded for improving resource efficiency—using less input to achieve the same or better output.

But Jevons Paradox suggests another outcome:

- A grower using See & Spray to reduce herbicide usage per acre may increase total passes, or apply pre-emergent products, too. Or shift to more premium, potent products because it’s now economical to do so.

- Variable rate technology may reduce fertilizer in some areas, but with incentives always to increase yield it often drives more fertilizer applied to the better producing areas of the field, keeping application totals flat or up.

Efficiency lowers the cost per unit, which often leads to expanded adoption or intensity of use— offsetting the initial efficiency benefits at a system-wide level.

Takeaway

Efficiency doesn't always lead to reduction—it can enable expansion. Agribusinesses need to be clear-eyed about how innovations ripple through farm behavior and market dynamics.